Old logic sees punishment as motivation. Good ‘ole school systems used this: strict rules and give anyone who diverges of the righteous path a good beating. That will see them right. I grew up in Britain which still had the cane (a thin stick) as a punishment in schools – it was finally abolished when I was 14, but not after my brother and been given a good whipping at school. To be honest that didn’t bother him so much, it was a badge of honour in a boy’s school – the proverbial beating my mother gave him was much worse (she was a teacher to boot).

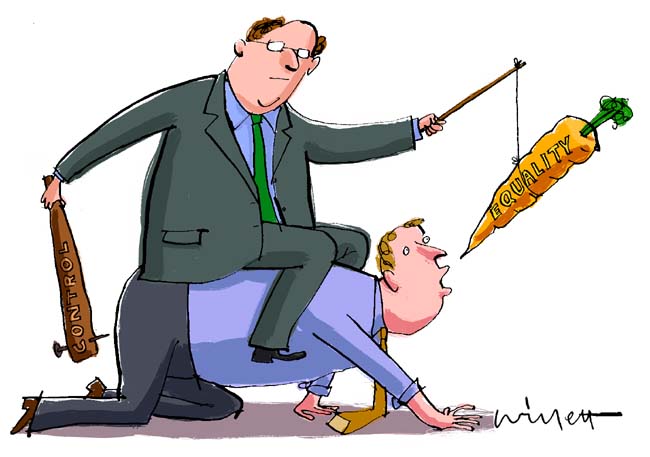

So, we see this pattern in society of severe punishment and this has slowly moderated over the centuries and recent decades. Now governments are using nudges and rewards to get people to behave in the right way. David Rock well known for coining term, neuroleadership, claims reward is the only path forward. Smacks of operant conditioning to me – was Skinner right all along? Doubtful – the brain, as always, will give us some answers.

The answers we need to first ask is that of motivation itself – if reward and punishment are seen as the means to an end i.e. a positive or effective behaviour, then we need to understand how the brain gets itself motivated. The research into motivation is long and complex and will break your patience for the moment, and break the page count for this issue, as interested as you may be. Short advertising interlude: We do give a short but comprehensive overview in our Brain and Behaviour Online courses. Interlude finished. Motivational research can be broken down into what (content theories) and how (process theories). But of most interest to us is the concept of approach and avoidance.

Approach and Avoidance

These are two motivational patterns well researched but of critical significance and still somewhat underrated in motivational research. Indeed, Elliot and Covington noted in an excellent, and still relevant, 2001 review that:

“… it is clear that the distinction between approach and avoidance motivation has deep and widespread intellectual roots, represents a part of the evolutionary heritage that humans share with organisms across the phylogenetic spectrum, is instigated immediately and automatically in response to most if not all stimuli humans encounter, is grounded in the basic neuroanatomical structures of the brain, and concords with the intuitively based knowledge of how humans are motivated in their daily lives.”

And go on to state:

“As such it is surprising that in much contemporary empirical and theoretical work on motivational issues, the approach-avoidance distinction is either overshadowed or overlooked altogether.”

To clarify, approach motivation is about moving towards, to achieve, to get something, and is reward driven. In our analogy it is the carrot. Avoidance motivation is about moving away from, protecting or fighting, it is the fear-based aversive form of motivation. In our analogy the stick – avoidance of punishment.

These two operate often in tandem – consider sporting teams who have a desire to win but also a desire not to lose. Both motivational directions are present. There is a tendency to see one as better than the other, but the fact remains that these are naturally present in all living organisms, so it is hard to justify one as being better than another – they are effective survival strategies which have been effective since the beginning of life and enabled all life forms to successfully propagate across the planet.

So now we have the motivational terminology for our carrots and sticks: approach and avoidance, let’s take a dive into the brain and see what this says about these forms of motivation before reviewing what this means for individuals, teams, and motivational strategies in, and out, of the workplace.

The Brain and Approach/Avoidance

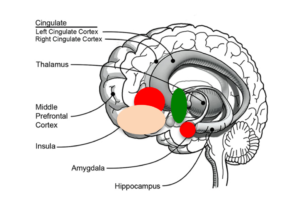

Research and brain scanning has shown approach is related to reward centres in the brain and avoidance is associated with fear/ threat mechanisms:

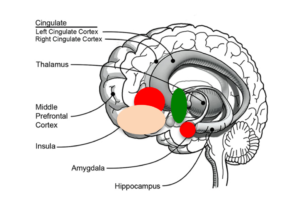

Regions for approach in green, avoidance in red, and both in pink

- Approach: ventral striatum (reward)

- Avoidance: amygdala, thalamus, insula (fear & threat)

Aupperle & Paulus in 2010 showed that the orbitofrontal cortex is involved with balancing these inputs. No surprise as the orbitofrontal is considered one of the main decision-making centres particularly for those decisions with emotional input.

- Orbital frontal cortex as decision making with inputs from ventral striatum modulating approach and inputs from Amygdala and Insula modulating avoidance

- Dysfunction of respective networks could predict susceptibility to specific anxiety disorders

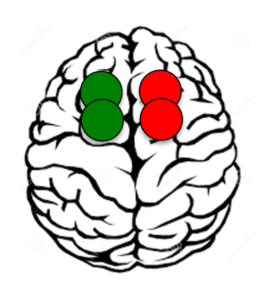

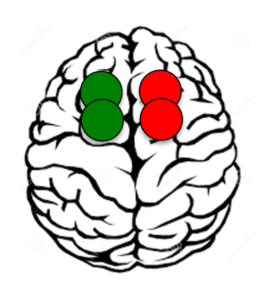

Spielberg et al. in 2009 found that there were hierarchical networks to do with planning and carrying out strategies and that these were hemisphere dependent. Planning being further forward in the brain – which would be expected as a more “frontal” function.

- Hierarchical networks

- System input from limbic regions and strategic integration at cortical levels

- Left frontal processes achieve goals / right frontal avoidance goals

Hierarchical processing for approach in left hemisphere and avoidance in right hemisphere

So far so good. We can see that approach motivation is reward driven and related to reward centres in the brain, and that avoidance motivation is fear and threat driven, and related to respective centres in the brain. We can also see that for planning and implementation these use different centres in the brain, and these are located in the left hemispheres for approach strategizing and the right for avoidance strategizing and planning. One side effect of this different processing in different centres is that this can cause motivational conflict – reward centres may need to fight it out with fear centres and approach and avoidance strategies can both be present in both our hemispheres. This is something we all have experienced – that tough decision when we are not sure if the upsides outweigh the downsides. This is our orbitofrontal cortex working hard and trying to figure out which one to choose.

What is also clear is that they both are natural mechanisms which are present to some degree in all human beings. But the question you may want an answer to is do these differ in human beings and if so how?

Individualisation

The short answer is, of course. These can be considered personality traits as much as evolutionary-based strategies. Some people will be more avoidance focused and others more approach focused. In personality this was first ascribed to the concept of extraversion and introversion particularly in social contexts. The extravert attracted towards, approach, social stimuli, and the introvert, avoiding social stimuli. Extraverts are also more sensation seeking, attracted to more stimuli. Similarly, sensitivity people, previously called neurotics, tend to avoid stimuli and are more anxious, that is avoidant.

We have reviewed these personality traits to build our Human Behavioural Framework, and this is another discussion for another day, but of interest are the psychometric scales designed to measure specifically measure approach and avoidance. The best known of these is the Behavioural Activation System and Behavioural Inhibition System Scale (BIS/BAS) developed by Carver at the University of Miami. These therefore measure trait approach/avoidance rather than strategic or situational approach or avoidance.

The research shows that there are three subgroups of approach motivation:

-

- Drive – achievement focus

- Fun

- Reward sensitivity

But now back to the workplace and the question of carrots and sticks. What does this tell us about reward and punishment? Firstly, it says that different individuals will respond and be motivated by different stimuli. Those high on BAS will respond stronger to rewards and stimulation. Those higher in BIS respond stronger to sticks. Though this may sound like I am suggesting that we just threaten and beat those high on traits BIS this is not true. These people will respond and do respond and see the downside or risk whether you like it or not. Interestingly they also respond strongly, according to other research, to safety – these are the people who need high safety to perform best because their threat-based systems, though causing action, will not enable them to function to their best.

No surprise that we come back to the concept of psychological safety that we have spoken about in other articles. The other important point being that those higher on BIS will not respond strongly to rewards – carrots don’t work as well with these people.

This points therefore to a more refined strategy of motivating individuals. Or rather the concepts of carrots and sticks works on average across a large population group because in a large population group there will likely be a balance of those more driven by reward and those more driven by inhibition. But the problem is that there will be large variations between individuals. This is therefore why knowing your people is critical to getting the highest performance.

Approach individuals, driven by reward and achievement, work well with stretch goals, rewards of different types, are not so fearful and so can manage pressure well.

Pictures like this have been shown to activate threat centres in the brain.

This simply means that team leaders will need to understand the individuals in their team to get the best out of them. Indeed, in our model of leadership this is precisely the role of the team leader – to understand the individuals in the team and to get the best out of them. This may mean taking a different approach with different individuals. Giving the sensitive individual safety, and giving the achievement individuals stretch, and some pressure, but appreciating them both, and managing effectively the contribution of all (see our article on Issue 2021-01 on team performance).Avoidance individuals, driven by fear and safety, work better in safe environments, are driven by fear but this can cause high anxiety and disruptions. They are less responsive to rewards.

A final note is that of short-term reward and short-term punishment. Short-term spontaneous rewards are very activating for the brain reward system. It’s simply an expectation thing – if you have an expected reward the brain responds very weakly to the reward – if you get an unexpected reward the brain responds very highly because it’s a surprise. So small, unexpected rewards are highly effective means of creating positive motivating effects. In financial terms a few small $50 rewards can be more effective than a yearly expected $5’000 reward – surprising but true. So spread your carrots out.

In contrast, short-term spontaneous punishment creates disruption, feelings of unfairness (which are very powerful in terms of motivation – equity theory), and disrupts orientation mechanisms. Punishment has to be clear: what it is for, why, and dealt out fairly. Simply put, there should, and must be, consequences to bad behaviour and violations of norms. But these should be rare – the punishment framework is a set of guidelines that people should avoid.

Psychological (and biological) punishment

Punishment from the brain’s perspective, however, comes in others forms, namely that of needs violation. Those of you inducted into SCOAP know that these five needs of Self-esteem, Control, Orientation, Attachment, and Pleasure form the basis of human beings. Leaders and those in authority often punish not intentionally, but often inadvertently in the form of needs violations: over criticism, putting people down, taking away control, or minimising pleasure. These are all actions that can be considered punishment from the brain’s perspective but are often not considered “formal” punishment. The seriousness of needs violation is supported by well-documented biological impacts, the first of which is increased stress, cortisol release (and whole set of behavioural changes and limitation of cognitive abilities), and the worst of which, over time, and if severe enough, are disrupted neuronal growth, and destruction of brain matter.

When I speak to business leaders about this they feel that they can no longer criticise people – I stress this is not about not focusing on performance issues. If someone underperforms, inform them quickly, respectfully, on precisely what, and enable them to perform better next time. Note, in addition, that some research has shown that confident people respond well to positive feedback but minimise negative feedback. Alternately those lower in confidence focus more on the negative feedback intended or not. That could be the subject for another article. This means that you may need to rebalance your feedback to individuals depending on their confidence and self-esteem ratings.

|

Stretch as a better predictor?

In developing our Human Behavioural Framework, we included many aspects – but as proposed by Carver, we see Behavioural Activation and Behavioural Inhibition as foundational personality traits that guide a lot of human behaviour. We therefore measure BAS/BIS using items from the BAS/BIS scale. This is not the same as the way we measured emotional responses to needs in the SCOAP-Profile as outlined above.

In a group of high-performing teachers one of the best predictors was not the height of these scales but the relationship. So, if BAS was higher than BIS it was a strong indicator of higher performance. These high-performing teachers were therefore less worried about negative affects, making mistakes, or failing. This is a similar pattern that we noticed in the corporate space also.

However, what is striking, and probably unsurprising, is the difference between start-ups and corporate leaders. We have a good set of data from startup founders and see that they are off the scale when to comes to BAS vs BIS. Their BAS ratings are very high, their BIS ratings are very low. Compare this to corporate leaders and we see these two converging – or even being reversed. This is interesting because some of these corporate leaders also claim to be “entrepreneurial” and suggest that their people or organisations should be more “entrepreneurial”.

We therefore compare these two ratings together because this is more predictive and call this “Stretch”. This is more predictive of performance we see but also of agile mindsets as outlined in article on agility.

|

Let’s summarise

Carrots – reward

- Small spontaneous rewards are very effective and underused in the corporate world

- Reward is particularly motivating for BAS (achievement focused individuals)

- Emotional needs fulfilment is the most critical aspect of deep reward (Self-Esteem, Control, Orientation, Attachment, and Pleasure). So, doing more of the cheap but important stuff like showing appreciation is more important than many assume.

- Large short-term rewards can increase stress and therefore decrease performance.

- Large long-term rewards with enough planning and preparation time normally increases quality and motivation.

- Creating a safe environment is critical for everyone but particularly for BIS (inhibition focused) individuals.

- A safe environment means a place where everyone can fulfil their needs, not feel threatened, and not have their needs violated or damaged by other team members.

Sticks – punishment

- Rather than punishment, think of requirements and guidelines

- Bad behaviour must be dealt with immediately and fairly

- Bad performance requires clear immediate feedback and enablement. Criticize the task and not the person.

- With confident people, they will minimize the negative feedback and focus on the positive (you may need to re-address the balance).

- Less confident people will maximise the negative feedback, and minimise positive. Focus on task and enabling the person.

- Short-term threats increase stress and reduce cognitive ability and normally reduce performance

- Shock effects only work when everyone has become complacent (how did you let it get this way in the first place?).

- Be careful of inadvertently punishing people by violating their SCOAP needs.

So, in short, the answer is, as usual, there is a bit of truth in the classic statement of using carrots and sticks but a careful review shows why and in what people. In team leadership it is therefore critical to know your people to enable high performance in the whole team. Carrots do work for the right people and some carrots are surprisingly effective but underused – the spontaneous small reward. Similarly, we should not think of punishing people but creating the guidelines for accepted behaviour and respond swiftly and appropriately when this is crossed – when it comes to performance issues, similarly a swift response, respecting the person and enabling high performance is critical. So, let’s call it carrots, fulfilling needs, and guidance●