What is SCOAP?

SCOAP is a complete model of human motivation, behaviour, and wellbeing, summarising over a century of research into the human brain and human behaviour in all contexts. SCOAP is an acronym for:

-

- Self-Esteem

- Control

- Orientation

- Attachment

- Pleasure

I will outline here what is included in these fundamental drives of human beings, what these can be used for, what the science behind these is, and importantly, how these relate to other theories.

The Disciplines included in the SCOAP Model

What is SCOAP for?

SCOAP is a complete model of human motivation, behaviour, and well-being, summarising over a century of research into the human brain and human behaviour in all contexts. This therefore means this is a model of:

-

- Human Behaviour

Why do we do what we do, what drives us over time, what engages us, what triggers us emotionally, and how we differ individually on these levels.

-

- Wellbeing

What we need for emotional and mental wellbeing and how these are related.

This therefore also makes it a model for

-

- Optimal performance

- Optimal learning

- Optimal brains

This can also be used in multiple contexts to stimulate optimal performance including:

-

- Business: organisational performance and well-being

- Business: team performance and well-being

- Sports: team performance and well-being

- Society: political dynamics

- Society: well-being

- Society: inter-group dynamics

- Education: optimal performance and well-being

- Personal: life satisfaction

- Personal: family dynamics

- Personal: relationship dynamics

For this short introduction we will focus mostly on business performance at the different levels (organisation, team, individual).

First, let’s understand what is included in SCOAP and how it contributes to motivation & motives, behaviour, and well-being.

SCOAP

SCOAP stand for the five core drivers and Needs of Self-Esteem, Control, Orientation, Attachment, and Pleasure. Each of these constructs are “big” constructs that cover various areas. For example, in Attachment we can consider relationships to our close family, to friends, to colleagues in the workplace, or society at large. One of the strengths of the SCOAP model is that the model has analysed over 54 other scientific models and synthesised these models into a coherent simplified model.

Here, in a simplified form, are Constructs (Facets) that fall under the Core Drivers (see evolutionary levels for more detail of the rationale behind these).

Various constructs that can be ascribed to the needs of SCOAP.

You will notice that many of these are key themes in leadership and motivational courses. These are often reported by other models as multiple drivers (e.g. any of the three-need models) or sometimes classed as a single key driver (e.g. love is all you need). We analysed 54 needs models and showed that these all nicely slot into SCOAP and it is better to see these as Facets of the Core Needs of SCOAP.

You may also be naturally attracted to some of these Facets and may feel that some are more important than others. However, we recommend not thinking of these in priorities, on average, because our research shows these are pretty evenly spread across populations. However, there will be individual differences. So, if you are an “attachment person” the concept of Attachment will resonate strongly with you. We explore this in the section on individualisation.

Another mistake is to class one as the primary motivation, or the “single key driver”. There have been many single driver theories throughout history, and they have contributed to the body of knowledge on human behaviour (and many were ground-breaking at the time) but we now know human beings are simply not so simple.

So SCOAP gives you a simple way to think of human behaviour by thinking of five Core Needs (and Drivers) which include numerous Facets and so cover the majority of human drives and desires.

1. SCOAP as Behaviour and Motivation

SCOAP gives us a simple model of human behaviour and motivation. The body of knowledge into human motivation is also wide and deep. The theories fall broadly into two categories. What drives behaviour and how it drives behaviour. SCOAP also integrates other aspects of motivation, namely motivational direction, equity theory, and how we update our motivational models (build Schema) over time. Some of this would require a deep dive into the theories, the science, and the respective models of behaviour.

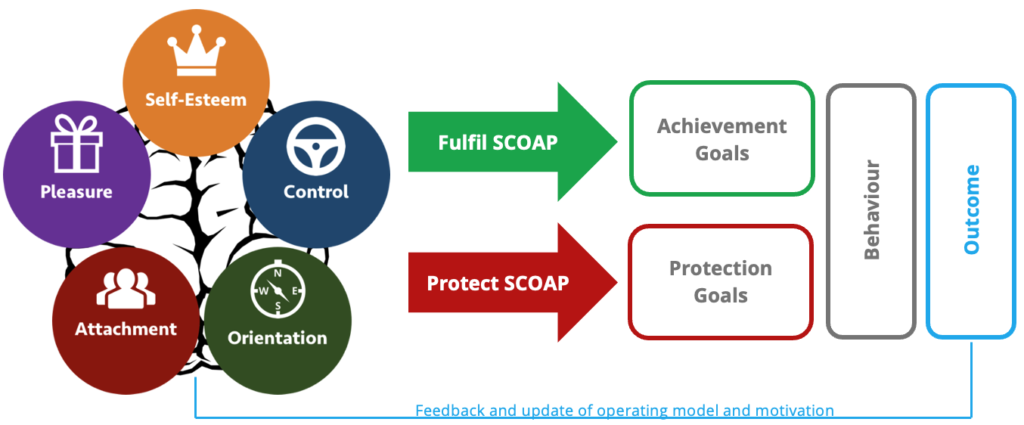

We define Motivation as an aroused state of goal pursuit.

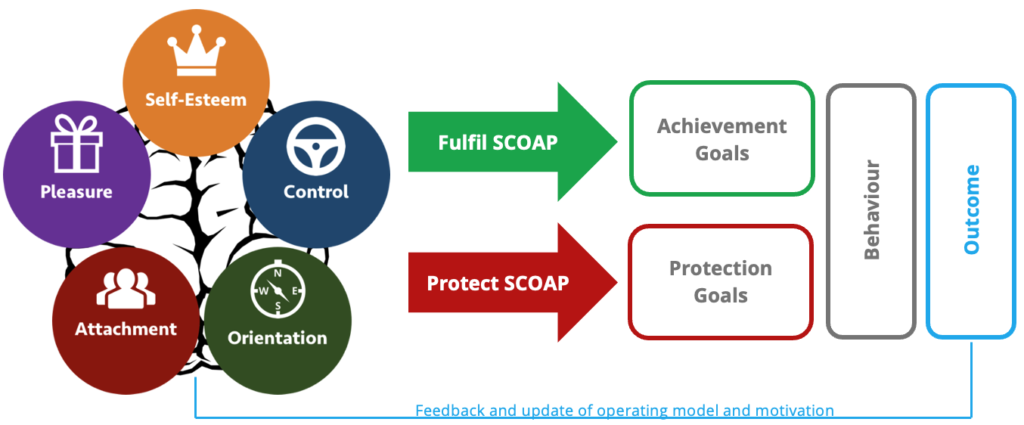

In this definittion of human motivation we are motivated to achieve goals. These goals are defined by our needs and personal ways we have defined these. it is also important to note that we may be motivated to achieve a goal, for example to increase status by getting abetter job, or to protect our needs by protecting our positions, ourselves, or thsoe close to us. this means we have two types fo goals Achievment Goals and Protection Goals. These drive our beahviour in our environemnts or context. Our motivioan has an outocme, nomralyl either succesful or unsuccesful. This then feeds back into our brain and understanding of the world and we will then set new goals (mostly unconsciously). We could then, for example, change the goal, or increase our energy, or change tactics. Here as an illustration.

The SCOAP model of human motivation.

Therfore in summary we say that all human beings are driven to fulfil or protect their Core Needs. This can include the following behaviours and motivations, with core needs listed:

-

- Do a good job: mostly needs of Self-Esteem and Control

- Move on in your career: mostly needs of Self-Esteem, Control, and Orientation

- Help others: mostly need of Attachment

- Win a sports match: mostly needs of Self-Esteem, Control, and Pleasure

- Be a good friend: mostly needs of Attachment and Pleasure

- Be a good parent: mostly needs of Attachment

- Take a qualification: mostly needs of Orientation and Control

- Have a good life: mostly need of Pleasure

This gives us goals, some of these are big life goals, but in daily business these are often smaller goals that may contribute to larger goals.

These goals then directly impact how we behave and what we do. This gives us an outcome that is either positive or negative. This positive or negative feedback will then lead to an emotional response and lead us to update our model and re-align our goals and our behaviour. For example, we may decide to increase effort on not reaching a goal, or we may decide to change our approach, or we may decide to give up.

For the record we should also distinguish motivation and engagement:

Motivation is the arousal and energisation of a person towards goal achievement (over time)

Engagement is the ability of the person to engage with the task(s) of motivated goal achievement over time (therefore includes other factors such as resources, prioritisation, abilities, processes, support).

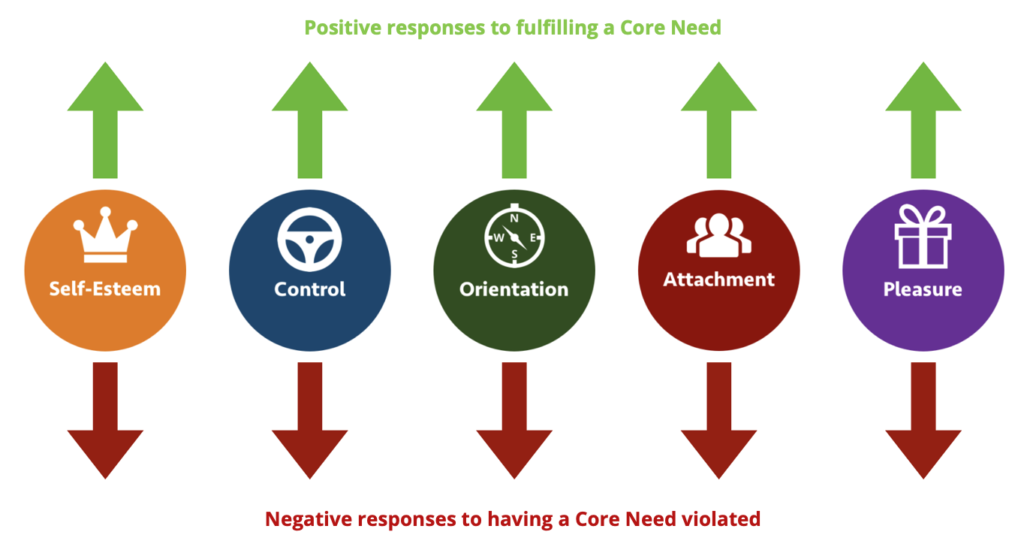

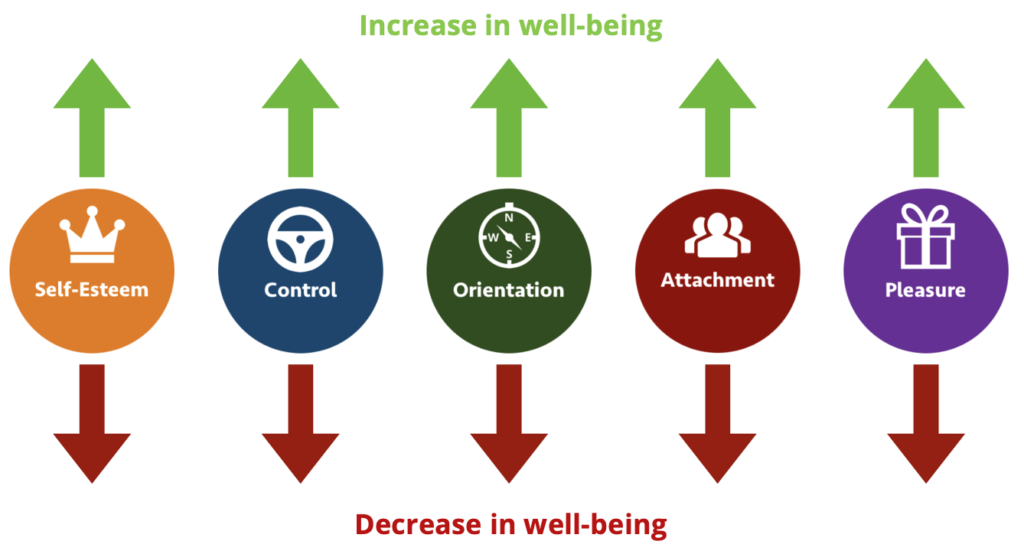

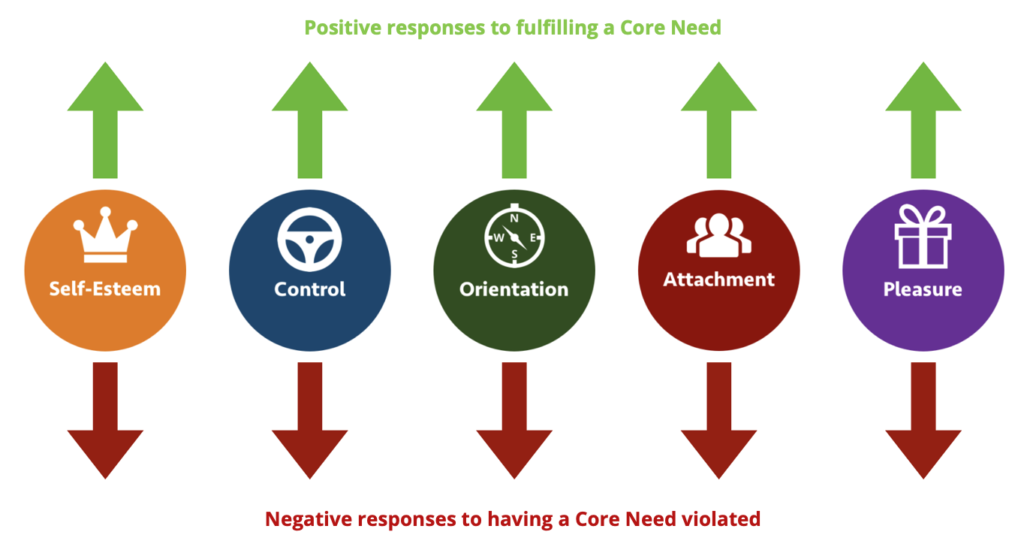

Emotional Triggers

We often use the term “emotional drivers” to describe SCOAP because this highlights the emotional and motivational aspect of these Core Needs. These Core Needs therefore trigger high emotional engagement but can also trigger high emotional responses and this can be positive or negative. We noted in the previous section motivation is about arousal and energisation. Motivational and leadership literature often talks of emotional triggers.

Fulfilling a SCOAP need (or multiple Needs) can trigger a very positive emotional response (see next section to understand the individualisation of this).

Damaging or having a SCOAP need (or multiple Needs) violated can also trigger a negative emotional response. Again, these will be individualised to varying degrees.

In the real world these come in different sizes and therefore have different impacts over different time frames.

| |

Life Feature |

Big |

Moderate |

Small |

Micro |

| Time scale |

Long-term |

Long-term |

Mid-term |

Short-term |

V. Short-term |

| Business |

Promotion to dream role |

Promotion / get the job |

Successful project completion |

Run a good meeting |

Be complimented on your work |

| Sports |

Win Major Title / Global Title |

Win Title |

Win a Match |

Have good training session |

Complete an exercise well |

| Family |

Get married / have a baby |

Child starts school |

Have a great holiday |

Have a special family meal |

Receive a compliment |

This illustrates that these can have impacts over different time frames, and different intensities, and in different domains. The above shows only positive events but you can easily think and imagine the impacts of negative events by reversing the above e.g. “fired from dream job”

Our personal model of Core Needs will define how strongly we respond to each Need (see individualisation).

Over time each of us may (and almost certainly will) build very specific triggers to specific scenarios “I hate/love it when…”

Our responses will also be moderated by our personalities e.g. some people are more sensitive and so respond stronger to fulfilment and violation of their Needs.

Individualisation

SCOAP gives us an outline of drivers of human behaviour on average. However, we are all individuals and will therefore relate to the SCOAP Needs and their Facets in different ways. This will be based on our natural personality, our upbringing, and our life’s experiences.

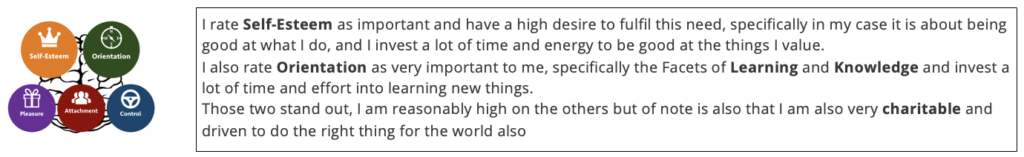

For example, my SCOAP Profile (Andy Habermacher) would look something like this:

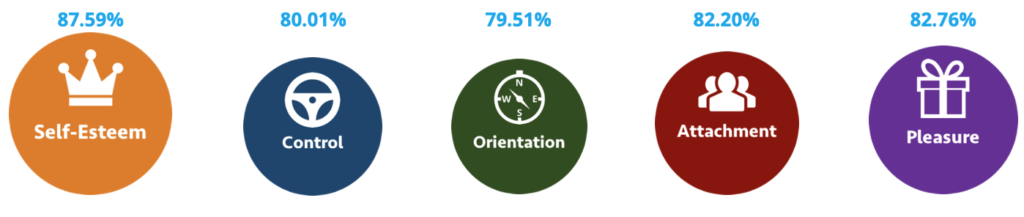

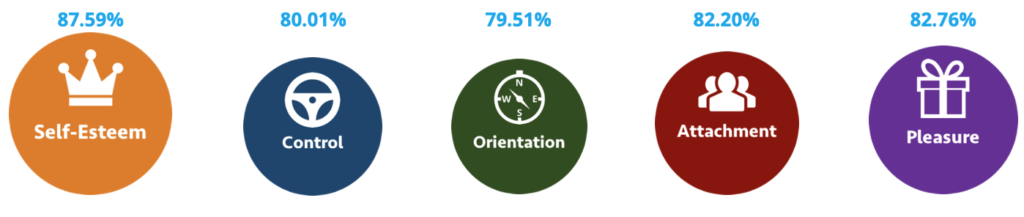

Our research shows that the Needs, based on the SCOAP-Profile in data collected in business between 2014-17, are valued as such*.

*Based on self-reported values on a scale of 0-10 or 0-100 and translated into %

This shows that most people rate Self-Esteem as their most important need followed by Pleasure and Attachment, then Control and Orientation.

Patterns

We have observed different patterns for individuals

Single Driver

People with single drivers focus very strongly on one Need and consider that life revolves around this. If you have this, you may have a clear life, or leadership philosophy. When we analyse some busines or leadership theories we can see that some of these have their roots in a one-dimensional view of human beings.

Double or Triple Driver

People with double or triple drivers will focus on multiple Needs and find them equally important or alternately find them the most important at different times. This will spread the focus but beware to be consistent. Again, some busines theories and leadership models focus on two or three drivers of human behaviour.

Balanced Drivers

Some people we measure, often high performers in business (but not only), showed very balanced and high Needs. This will make them engaged and motivated across all Facets and Needs. Hence the ability to commit a lot of energy and be constantly motivated. It can also make these people more sensitive to the up and downsides.

Peaks and Troughs

Some people have very high variation, sometimes within a Core Need. These people are often considered to be “high on personality” i.e. they can be seen as “special characters” because of their very strong drives or complete indifference to certain Facets of Needs. These people can be loved or disliked, probably because of their “eccentricity”.

Influence of Personality

Our personality traits will contribute to how these Needs are processed and expressed. For example, introverts may not express as clearly or emotionally their feelings and whether their Needs are fulfilled or violated. Similarly, those higher on sensitivity will respond stronger to need fulfilment or violation. We also showed in some workplace research that this contributes to well-being, and energisation in the workplace (see next section).

2. SCOAP as Well-Being

The base theory of SCOAP was built on a model of mental health and optimal human health by Klaus Grawe who proposed his Consistency Theory Model in 2004 (2007 in English) while writing on neuropsychotherapy. This summarised multiple lines of evidence and research to show that violation and lack of fulfilment leads to diminished well-being and risk of mental health disorders, and increasing fulfilment leads to better well-being and reduction of mental health disorders. In fact, he said:

“This suggests that well-being depends almost entirely on the degree to which individuals manage to attain their motivational goals”

In “motivational goals he is referring to fulfilling emotional Needs that we have reformed, reanalysed, and restructured into SCOAP. We have further refined this by measuring Needs fulfilment in an individualised way i.e. In comparison to one’s own personal model of SCOAP.

Ghadiri showed in a piece of research in 2017 that measuring mismatches in SCOAP, combined with personality traits, was a much better way to predict well-being and fatigue in the workplace.

So, simply put, if your workforce can, on average, fulfil their SCOAP Needs to a suitable degree they will be satisfied and have high well-being. This will enable them to commit their energy and cognitive resources. They will therefore be in a position to perform to the best of their abilities. Whether they can, or cannot, will depend on some other factors such as alignment and resources (but this will also be reflected in SCOAP feedback).

SCOAP is far from unique in ascribing well-being to human Needs. Many needs models are designed as models of human well-being, in and out of the workplace. SCOAP, however, is a balanced and comprehensive model and also measures individualisation of the Needs and therefore gives better data.

In short SCOAP is the most robust, comprehensive, and indivdualised model there is.