No Results Found

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.

. . .

This content is only for Premium Brains - please subscribe to access this. All subscriptions come with a free trial.

Register for free to receive access to "Healthy Brains" and other selected articles.

Subscribe to Premium Brain (monthly or annual) to access all articles and access the download page.

Subscribe now

. . .

This content is only for Premium Brains - please subscribe to access this. All subscriptions come with a free trial.

Register for free to receive access to "Healthy Brains" and other selected articles.

Subscribe to Premium Brain (monthly or annual) to access all articles and access the download page.

Subscribe now

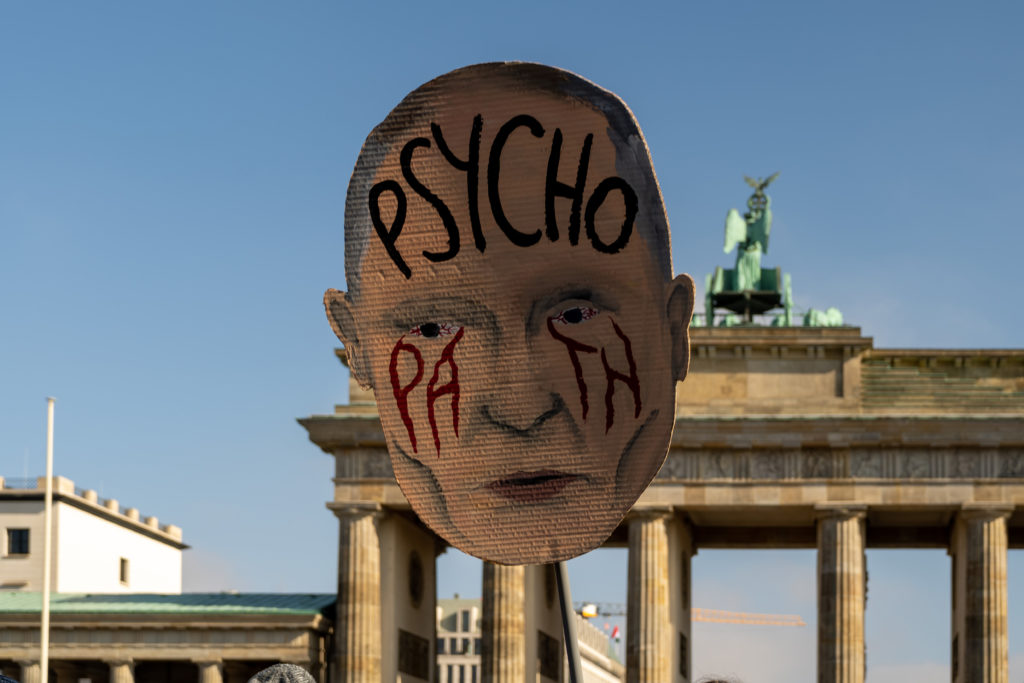

There has been a lot written about Putin and Russia over recent days and weeks. Many of them have been spot on. I would like to add to this in my field of expertise, the human brain, and this will highlight just what we are dealing with and the challenges.

Somehow the world was surprised when Russian soldiers marched into Ukraine. Indeed, a think tank had reported just a few weeks previously that the chance of a Russian invasion as less than 50% – they obviously said that it was probability – in retrospect maybe that figure should have been closer to 100% as it is now clear he was always going to invade. Indeed, those neighbouring countries had been warning the West for a long time – the invasion to them was not a surprise, a simple inevitability. I sadly admit my prediction that he will invade directly after the Olympics also proved to be spot on – why were some of the predictions wrong (they all thought they could be wrong, I know)? It lies in the simple fact they were classing “rational” ideas such as damage to economy with benefit of Ukraine – they weren’t thinking of how a Machiavellian Psychopath like Putin thinks.

So, what is happening in the brain of Putin? It is relatively easy to explain when we understand some of the dark traits of personality. And this is what I will outline in this feature article.

So, let’s look into dark personality traits. The dark triad is a term used to refer to a triad of personality disorders associated with bad, toxic, and plain evil behaviour. For those regular readers of leading brains Review, I also summarised this with respect to toxic leadership in lbR-2021-06. The dark triad are:

Colloquially we tend to think of psychopaths as those heartless criminals – and this is true, these are the classic Hollywood supervillains, creating evil plans with no remorse at killing others and playing the dirtiest of dirty tricks. Indeed, an intelligent calculating psychopath is dangerous, very dangerous, indeed. And it is in psychopaths that there has been a lot of research, and brain scanning research at that.

The Dark Factor of personality

The dark triad is an easy way to remember these dark personality traits, but more recent research has come up with a more useful way of describing these. Rather than thinking of all three as separate entities and disorders Moshagen, Hilbig, and Zettler, in 2018, proposed the D-Factor. They noted that there is a strong interplay between all of these, and we can therefore think of one D-Factor score with different preferences or flavours of this. This makes sense, but this was a big thing to say at the time. They note nine characteristics of the D-Factor:

The D-Factor is more useful I think because it also shows some of the other factors that may or may not be associated with the dark triad such as sadism or spitefulness. In the 2018 paper Mohagen et al. summarise succinctly the D-Factor as:

“…the tendency to maximize one’s individual utility—disregarding, accepting, or malevolently provoking disutility for others—accompanied by beliefs that serve as justifications”

This is however, a more recent concept and if we want to look inside brains, and particularly Putin’s brain, we need to revert to multiple older studies and reviews on, primarily, psychopaths.

So, can we identify a psychopath from their brain activation patterns? The answer is easy: yes, we can.

Brain activation

Brain scanning in psychopaths started in the noughties and has developed ever since. In parallel the understanding of psychopathy have also developed with a clearer understanding of what it is and also differentiations with the criminally intent and the not criminally intent. In recent years there have been a number of reviews and meta-analyses of studies to give clearer understanding. Brain scanning aims to identify what are called primary psychopaths – those that are born with the structural differences that give rise to psychopathy and can be identified in children very early on – yes, as early as 2 or 3 years old!

I’m sure you’re itching to understand what is happening in the brain and how we can see this so early – and whether this pattern is reflected in Putin and his brain and whether we can do anything about this.

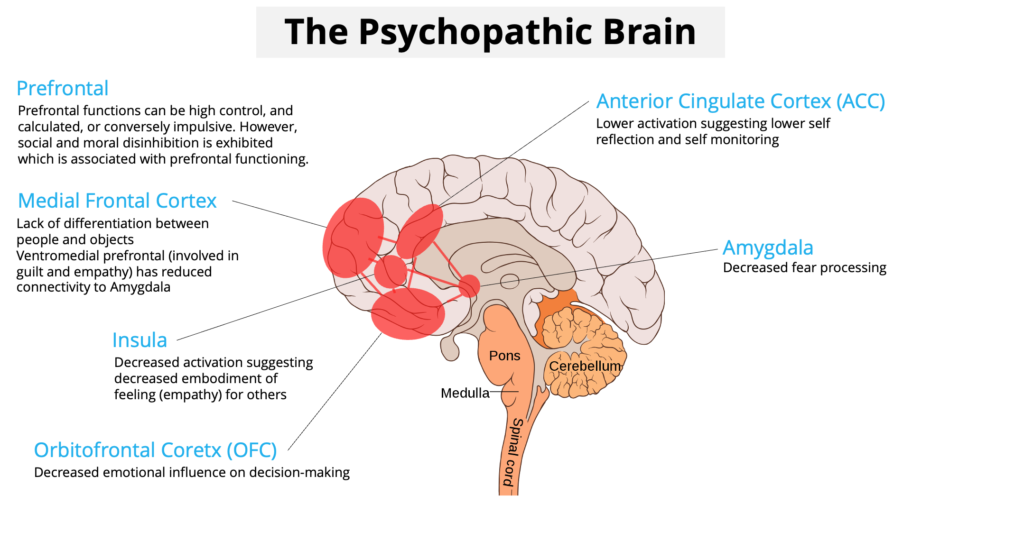

The first things that jumped out in brain scanning studies was that an area called the amygdala, that is strongly involved in fear processing, but also all emotional processing. This shows decreased activation to emotional stimuli – this falls in line with being cold and fearless – brains of psychopaths do not process fear or emotions in the same way as a non-psychopathic brain.

Prefrontal to emotional connectivity is another area that is reduced. For regular readers of my writing, you will know that the prefrontal areas of the brain are involved in the more cognitive rational functions of the brain. This drop in prefrontal connectivity, particularly in an area called the orbitofrontal cortex, reduces the impact of emotions on decision making, leading to those cold utilitarian decisions.

These are the big two but there are also other areas. Readers of leading brains Review will already have been introduced to these areas and their functionality. An area called the insula is also activated differentially – the insula is an area that is involved in embodiment of feelings, such as pain and disgust but also feeling for others. This suggests reduced empathy for others.

Another area identified in one study in anti-social people was in a region known as the medial frontal cortex. This is a region in their fontal lobes of the brain that is involved in social processing. In this region there was little difference shown between processing people and objects – the takeaway here is that some people fail to differentiate between human beings and objects, effectively seeing people as objects. If you are a grandiose narcissist or psychopath, as your objects, or objects for your use.

And finally, an area called the anterior and posterior cingulate cortex shows less activation. This is an area that is associated with error detection but also internalisation and self-reflection. This therefore suggests less internal reflection or reflection on one’s own actions. These people are not self-reflective.

All of this points to a very specific brain in those high in D-Factor. Which matches perfectly to those traits outlined by Moshagen et al.

Note this is not “psychological”, this is hard wiring in the brain. This show that they process fear differently are cold and calculating, have little empathy, see people as objects, most likely for their own personal gain, and are not self-reflective. This is “hardwired” and can be seen in young children.

Nature and/or Nurture?

So, this is the nature of a psychopath but how much of this can be changed? The brain is after all plastic and responds to its environment. This is relevant to Putin and his brain because nature alone may not be sufficient, but both nature and nurture together could be disastrous.

For that we should go to the story of Jim Fallon a neuroscientist who was studying brain activation patterns of psychopaths in 2005. On one study he was comparing brain scans of psychopaths to a control group. This particular control group was that of his family – easy and cost effective to organise. On looking through the control group scans he noticed an activation pattern that was clearly psychopathic. Clearly there had been a mix up – he asked his lab assistant to check on the mistake and assign it to the correct group – however the answer came back it was in the correct group. He then asked for the identity of the scan – which he could do as they were of himself and his family. To his surprise, and shock, the brain scan of that psychopathic brain was his own!

For the in and outs of this you may want to read the review in the Atlantic or in other places (a fascinating read). But the question we then need to ask is how can a psychopath become a successful neuroscientist – or is this common indeed?

The first question is that certain traits of psychopathy are actually beneficial and even celebrated in certain cultures – think of the hard-nosed business person. But your environment can also have a big effect. Jim Fallon notes the positive effects of his upbringing – his educated, relatively affluent middle-class upbringing gave him good guiderails to do the right thing and engage in the world in the right way. But he noted on reflection – which is not something that comes easy to him, and in conversation with those close to him, that yes, he could be an arse, or simply psychopathic. Which of course he initially denied, as a psychopath would, and blame other people. But he is trained in neuroscience and has the cognitive ability to process this and process this he did. He therefore made an effort to become less psychopathic, with some success. He noted, however, that he was just going through the motions of being a nice person. Those around him however, agreed wholeheartedly, that they would much prefer he went through the motions than being an arse.

So, what does this tell us about environment? Firstly, environment can give support and guidance to those high in psychopathic or D-Factor traits to behave in suitable ways and become successful and non-criminal. There is a body of research into so-called successful, or non-criminal psychopaths, but space won’t permit going into that here – we after all want to get onto Putin’s brain.

Fallon himself at that time spoke of primary and secondary psychopathy. Primary being those hard-wired brain patterns that you can see very early on and secondary as the environmental factors pushing people into psychopathy. So, psychopathy can be inborn and can be mitigated by good upbringing or a suitable environment and society. And an unsuitable upbringing and local environment can push people into criminal psychopathy.

What does this mean for Putin – with no brain scans at hand and only observational evidence? Well, it is still pretty clear (crystal clear actually) where Putin stands. He clearly falls as primary psychopath or high on D-Factor traits and his environment has supported and rewarded this – remember he is ex-KGB.

This brings us on to two other factors which help to magnify D-Factor traits and others are present in Putin – in heaps.

Position Magnifies Psychopathy

Admittedly that title may be a little exaggerated, but it catches your eye and there is some truth in it. Why do I say that? Well, an interesting study I reported on last year, and was one of my most popular Quick Hits, looked into how peoples’ opinions and decisions change with positions of power – in this particular study, in supervisor positions in business-related scenarios. This experiment was interesting because it took the same people and then they made judgements based on their position. And lo and behold those in supervisor positions, where they had more power, and more choice, judged people more harshly, and were more willing to punish people for transgressions, and were less forgiving. Power corrupts, as they say.

Obviously not everyone, and not excessively, but the fact is, if you are in position of power, you are more likely to be less empathic, more judgemental, and harsher. Sorry to say. In society this also comes with wealth and privilege where you have more choice either through social influence or through finance – which you will likely take for granted. The authors called it a “choice mindset” – when you have the ability of choice through your position in business or society, it is easy to over-estimate how much choice others have and therefore judge them more harshly. Another one politicians and voters should be aware of.

However, I digress a little, what this shows is that positions of power will magnify D-Factor traits and they may appear where non appeared before. Don’t get me wrong this is not for everyone – nice people will still remain relatively nice – but psychopathic will likely become more psychopathic.

There is another factor that is interrelated – it is based on worldviews. Worldviews are a complex psychological phenomena that influence our whole view of the world and how it operates. They are basically our operating system and are based on multiple assumptions of what is good and bad, human nature, etc, etc.

There are simplistic ways to describe this as outlined in the 1950’s by the legendary Tomkins and his Normative and Humanistic worldviews which aligns pretty neatly with the conservative (normative) and liberal (humanistic) worldviews. Politicians and the general public would be well-advised to educate themselves in this – it explains a lot of politics especially in the USA.

There are more complex version of worldviews such as Pepper’s unreconcilable worldviews whereby Pepper proposed that many of the big conflicts in society are not actual conflicts but a result of different worldviews that are not reconcilable. Also, an insightful read. But for a full review of the concepts and complexity of worldviews you should read Koltko-Rivera’s review from back in 2004 – but back to the issue at hand. Putin and his invasion of Ukraine.

Here we can see that Putin is operating from a clear worldview. A worldview that power is defined by physical and military power. That the greatness of a nation is defined by its ability to coerce and manipulate other countries. That greatness is defined by the territory that you own. That is Putin’s worldview. He operates in this world, and this is also subject to ratification because he will use all these malicious methods to spy, coerce, and influence and if anyone retaliates or spies on him it just reinforces his world view.

His worldview seems to, clearly, be that of the old Soviet KGB spy. A great Russia is a big Russia, A great Russia overpowers their neighbours. A great Russia is in control. A great Russia will destroy you if you do not obey.

Putin cannot imagine, is not capable of imagining, another Russia, a Russia that could be great through peaceful things like generating great science, great art (which Russia consistently has done), or through wielding soft power and positive influence. Putin cannot imagine this; his worldview will block this. His brain will not allow this.

Putin’s Brain

So back to the original question of what does Putin’s brain look like and what we can predict he will and won’t do?

First off, we can safely say he is a primary psychopath or very high on the D-Factor. He exhibits all of these features in abundance. But some psychopaths are hot-headed and impulsive. He is not. He has enough cold calculating power to think long into the future and control his actions to get the absolute best for himself and Russia – but mostly for himself. That is a feature of psychopaths like Putin – it is primarily driven out of self-interest. He is interested in a great Russia but more as justification and to drive his ego, but also to influence others, more than he really cares for Russia. In his mind he is Russia, and a great powerful Russia at that.

So, combine his brain which is wired to have minimal empathy for others, to be cold and calculating, to be self-interested, not to mention sadistic and spiteful, with his environment, cutting his teeth in the KGB. The right environment to reward all those psychopathic tendencies he has – but as I said, with enough cold calculation to also play the long game. Combine this with his position as President, now for life – meaning he does not have to face voters even in a Russian sort of manipulated way. And combine this with his worldview and we have a perfect storm.

A brain designed to be psychopathic, built in an environment which is conducive to psychopathy, reaping the rewards from his behaviour, in a position of power which magnifies these features, and with his worldview. Oh dear, oh dear, oh dear.

The predictability of Psychopaths

Now some may think that Putin is unpredictable, but the fact is he is very predictable. We know the features of his personality and how he will respond. What we confuse is our worldview with his worldview – we may see the world through more rational eyes, through more reasonable eyes, more compassionate eyes – so we will not ”understand” Putin. In the West we have not been completely naïve, but we have failed to understand how far he will go. How far will he go?

He will go all the way.

You see he is a cold-hearted psychopath in a position of absolute power with a certain worldview. What does this mean for the Ukraine.

It bodes very darkly, and the West would need to sit up and pay attention now – and I mean now.

At this stage of the conflict Putin will make sure that Ukraine is destroyed by any means possible – if he can’t take it, it will be destroyed.

I do not say the above lightly. I do not say the above because I do not believe in peace. I personally think it would be so easy to live a peaceful pleasant life – but the fact is, there are Putins in this world and I am no longer naïve to that fact. And he will do as I have outlined above. It is in his nature, his upbringing, his position, and his worldview.

How do you fight a psychopath?

Now the question comes of how you fight such a psychopath as Putin. The answer is, with difficulty, but it can be done. The biggest mistake in fighting psychopaths is not building a very powerful, very aligned coalition. You see those high in D-factor, particularly those that are calculating, are very good at manipulating the system and taking out single threats. One person stands up and is immediately taken out – this serves as warning sign to others, who may think of standing up, that they will suffer and not survive – it is to silence the majority.

So:

Even if this works, I may be that the psychopath will hold resentment against you for your life. This is why it is best that the voice comes from the collective to create a diffuse enemy and not a concrete easily identifiable one.

How to beat Russia in Ukraine?

As I write this, this may be too late, I am more than aware of this. It could be all over when you read this, but it may still help you to understand how it could have been avoided.

Thinking of Russia in Ukraine – first Putin wanted to take Ukraine for his own benefit. As I have outlined, he has no care for the lives of the innocent in Ukraine or in his own military. He expected a strong response from the West but nothing that would stop him taking Ukraine. How to stop him now?

Why China you may ask – because China is Russia’s lifeline at the moment. No China, and Russia essentially loses all meaningful influence and all trade.

Will Putin use nuclear weapons?

I will stick my head out here and say something we all never wanted to hear. I think Putin is likely to use a nuclear weapon. Why?

In short, if he can’t take Ukraine, the chance of him nuking Kiev, for example, are very high. Sorry to say.

The walrus fight

The concept of a walrus fight is one I use to explain situations like this. In the world of walruses if you don’t fight, your lineage dies. One male walrus will control and have mating rights with a harem of females – for another male to get mating rights he will have to beat another male. And boy this male will fight it out. So, a young male will have to pick their fights carefully but when it comes to it, at some stage, they have to go all in – if you don’t, you lose, and if you are not willing to go all in, you have no chance of winning – you have lost from the outset. It is about the future of your lineage. You have to be prepared to go all in – be strategic yes, be clever yes, but at some stage you will likely have to fight, and the other walrus will have to believe this.

I see Ukraine as Walrus Fight – a fight that will have ramifications for many generations to come – a ceding of power to the East. A restart of nations taking over other nations by forceful means – unless there is a walrus to stop this. And there is – so far, they have not shown the appetite to go all in. They have not understood that this is a Walrus Fight. A fight for their future lineage.

So, what can you do as in individual feeling powerless?

Back to the brain

I do not want to advocate war or aggression – I believe in peace and collaboration and being nice to each other. But the brain and all research into Dark Triad traits and disorders, and the D-Factor, show that with some people you will be left with no option. Putin’s brain does not have the wiring to be reasonable and compassionate. This pattern of activation has been magnified through his upbringing and his career in the KGB, and in his position as President for Life. He has consistently shown these traits and has shown how little he cares for human life and moral codes. He doesn’t care because his brain does not have the wiring to care – he does not have the worldview to back this up, in fact his worldview is the opposite. He will aim to increase his power at all costs.

This is tragic, tragic for Russia, tragic for the Ukraine, and tragic for us in the West. There is a way to stop him and that is tough, but if we don’t, we still have a powerful psychopath on the loose, and a further empowered psychopath at that, that will continue to operate as he has done, potentially with more aggression, vindictiveness, and cruelty.

Sorry to say. But that is Putin’s brain●

Andy is author of leading brains Review, Neuroleadership, and multiple other books. He has been intensively involved in writing and research into neuroleadership and is considered one of Europe’s leading experts. He is also a well-known public speaker speaking on the brain and human behaviour.

Andy is also a masters athlete (middle distance running) and competes regularly at international competitions (and holds a few national records in his age category).

D-Factor

Hilbig, B. E., Thielmann, I., Klein, S. A., Moshagen, M., and Zettler, I. (2021). The dark core of personality and socially aversive psychopathology. J. Pers. 89. doi:10.1111/jopy.12577.

Moshagen, M., Hilbig, B. E., and Zettler, I. (2018). The dark core of personality. Psychol. Rev. 125, 656–688. doi:10.1037/rev0000111.

Moshagen, M., Zettler, I., and Hilbig, B. E. (2019). Measuring the Dark Core of Personality. Psychol. Assess. doi:10.1037/pas0000778.

Zettler, I., Moshagen, M., and Hilbig, B. E. (2021). Stability and Change: The Dark Factor of Personality Shapes Dark Traits. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 12. doi:10.1177/1948550620953288.

Dark Triad

Giammarco, E. A., and Vernon, P. A. (2014). Vengeance and the Dark Triad: The role of empathy and perspective taking in trait forgivingness. Pers. Individ. Dif. 67, 23–29.

Jakobwitz, S., and Egan, V. (2006). The dark triad and normal personality traits. Pers. Individ. Dif. 40, 331–339.

Kaufman, S. B., Yaden, D. B., Hyde, E., and Tsukayama, E. (2019). The light vs. dark triad of personality: Contrasting two very different profiles of human nature. Front. Psychol. 10. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00467.

LeBreton, J. M., Shiverdecker, L. K., and Grimaldi, E. M. (2018). The dark triad and workplace behavior. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 5. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104451.

Muris, P., Merckelbach, H., Otgaar, H., and Meijer, E. (2017). The Malevolent Side of Human Nature: A Meta-Analysis and Critical Review of the Literature on the Dark Triad (Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and Psychopathy). Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 12. doi:10.1177/1745691616666070.

Paulhus, D. L., and Williams, K. M. (2002). The Dark Triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. J. Res. Pers. 36, 556–563. doi:10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00505-6.

Trahair, C., Baran, L., Flakus, M., Kowalski, C. M., and Rogoza, R. (2020). The structure of the Dark Triad traits: A network analysis. Pers. Individ. Dif. 167. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2020.110265.

Psychopathic Brain

Anderson, N. E., and Kiehl, K. A. (2012). The psychopath magnetized: Insights from brain imaging. Trends Cogn. Sci. 16. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2011.11.008.

Beeley, C. (2006). The Psychopath: Emotion and the Brain. Secur. J. 19. doi:10.1057/palgrave.sj.8350013.

Glannon, W. (2014). Intervening in the psychopath’s brain. Theor. Med. Bioeth. 35. doi:10.1007/s11017-013-9275-z.

Konicar, L., Veit, R., Eisenbarth, H., Barth, B., Tonin, P., Strehl, U., et al. (2015). Brain self-regulation in criminal psychopaths. Sci. Rep. 5. doi:10.1038/srep09426.

Lenzen, L. M., Donges, M. R., Eickhoff, S. B., and Poeppl, T. B. (2021). Exploring the neural correlates of (altered) moral cognition in psychopaths. Behav. Sci. Law 39, 731–740. doi:10.1002/bsl.2539.

Pera-Guardiola, V., Contreras-Rodríguez, O., Batalla, I., Kosson, D., Menchón, J. M., Pifarré, J., et al. (2016). Brain structural correlates of emotion recognition in psychopaths. PLoS One 11. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0149807.

Poeppl, T. B., Donges, M. R., Mokros, A., Rupprecht, R., Fox, P. T., Laird, A. R., et al. (2019). A view behind the mask of sanity: meta-analysis of aberrant brain activity in psychopaths. Mol. Psychiatry 24, 463–470. doi:10.1038/s41380-018-0122-5.

Santana, E. J. (2016). The brain of the psychopath: A systematic review of structural neuroimaging studies. Psychol. Neurosci. 9. doi:10.1037/pne0000069.

Yang, Y., and Raine, A. (2009). Prefrontal structural and functional brain imaging findings in antisocial, violent, and psychopathic individuals: a meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 174, 81–8. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2009.03.012.

Weber, S., Habel, U., Amunts, K., and Schneider, F. (2008). Structural brain abnormalities in psychopaths – A review. Behav. Sci. Law 26, 7–28. doi:10.1002/bsl.802.

van Dongen, J. D. M. (2020). The Empathic Brain of Psychopaths: From Social Science to Neuroscience in Empathy. Front. Psychol. 11. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00695.

Jim Fallon

https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2014/01/life-as-a-nonviolent-psychopath/282271/

Position and Judgment

Yin, Y., Savani, K., and Smith, P. K. (2021). Power Increases Perceptions of Others’ Choices, Leading People to Blame Others More. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. doi:10.1177/19485506211016140.

Worldviews

Stone, W., and Schaffner, P. (1997). The Tomkins Polarity Scale: Recent Developments. Bull. Tomkins Inst. 4, 17–22. Available at: http://tomkins.org/uploads/polarityscale.pdf.

Lee, D. S. (1983). Adequacy in World Hypotheses: Reconstructing Pepper’s Criteria. Metaphilosophy 14, 151.

Koltko-Rivera, M. E. (2004). The Psychology of Worldviews. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 8, 3–58.

Self-love sounds like a good idea but it can be double-edged sword. Narcissism is clearly not a positive trait, and on the other side self-criticism can help you grow. I explore the ups and down and probably what we mean by self love.

I went through a phase of going to meditation courses and groups a few years ago. It did me good I am sure – I have read the science. It certainly felt good at times. Funnily enough my desire to meditate slowly evaporated as I worked more with the SCOAP model and that is insightful in itself. During these meditation sessions a common theme was love thyself, self-compassion, and not beating yourself up. Interesting is that these were proposed as if this was the natural state of affairs. Which can lead us to surmise that 1. not loving yourself is the standard nature of human beings, or alternatively 2. not loving yourself is a common feature of those who are attracted to meditation.

Indeed, if we read online motivational blogs, self-criticism is a common theme – so indeed it does appear to be considered a key theme and therefore common. However, in trying to review the academic literature to get a grip on how common this is, I found it difficult to find any solid research to give an indication of how widespread this is. However, some work I did on the SCOAP model and self-esteem may give us something to get a grip on.

In our data on SCOAP we found that the desire for Self-Esteem was consistently ranked as the number one need therefore making this the most important human need on average. This is interesting because it shows that we have a high desire for self-esteem, and this is consistent in human beings. But what is also interesting is that if this Is rated highly it also means that damage and non-fulfilment is also likely to cause disruption. If I want high self-esteem and don’t achieve it, it will cause a mismatch – and therefore also an emotional reaction. Dissatisfaction or frustration of sorts. So, in short, self-esteem appears to be our most powerful need meaning we are most sensitive to damage or threat to it.

Also, within self-esteem there are multiple factors at play which I have analysed in much more detail in my analysis and presentation at the BPS Coaching Psychology Conference in 2015 – first, is that there is a strong social component, something called the Sociometer (first proposed by Leary et al. in 1995). We tend to rank ourselves against others and through we may blame society and systems in society – this is unfair, we do it automatically, it is instinctive. We do compare ourselves to others no matter how often we say, “Don’t compare yourself to others”.

This comparison though, goes through different stages, with teenagers being particularly sensitive to various social comparisons. To be embarrassed is a big thing in teenage years, as my teenage daughter keeps telling me. As we age this becomes less important and we become less sensitive to various forms of showing ourselves up. Of note is also what is known as the spotlight effect, which teenagers are particularly sensitive to, is that we overestimate how much attention people take of us, as shown neatly in an experiment by Gilovich et al. in 2000: he got youngsters to wear a yellow Barry Manilow t-shirt (yes, that bad) to a gathering and then measure how many people remembered or noticed this. The result was hardly at all. In stark contrast to how the t-shirt wearers felt.

But a problem with this social comparison is that it can lead to the majority of the population being self-critical or believing they are sub-par. Though we do tend to have an overconfidence bias in many areas – we believe we are above average, on average, most of the time, we may also be sensitive to the fact that we are not amongst the best in any domain. This is because we naturally look upwards – many of you know I am a competitive athlete and my 800m running time in 2021 was 50th best in the world in my age category. Was I happy with this? No, I wasn’t! I am now looking to be in the top 25, no mean feat, but my natural ambition and dedication means that I am now measuring myself not in terms of top 100 in the world, and not even the top 50, but the top 25 – that gives me plenty of room for self-criticism and musing on whether I really have the ability to get there.

The other side of self-criticism is also that to move on and be good in life we should be critical – in my running I could be happy with being in the top 50 in the world or I can set my ambition to be in the top 25 – if I set my ambition to be in the top 25, I am more likely to improve than if I sit on my laurels and pat myself on the back for my performances in 2021. So, in this context self-criticism, at some level, is a good thing. It drives individuals forward, on a cycle of ever improving and reaching higher heights. And indeed, some of my best performances have come after a bad performance where I have beat myself up about my own inability. A contradiction? Maybe.

So far:

So, with this, what about self-criticism? Is this a good or bad thing? Well, the research seems to show that it is a bad thing – though it may drive a number of us onto higher performances, it also drives more people into despair, frustration, and general feelings of low self-esteem. Being self-critical is considered a risk factor for many psychopathologies and research has shown that those who score high on self-criticism have worse outcomes in therapy.

So, it seems that more self-love is in order – and research mostly into meditation shows that self-compassion seem to be a route to this. Forgiving oneself rather than not criticising oneself in the first place. It could also be that self-criticism is no bad thing but that rumination, the act of dwelling on this is likely to be the key culprit. Being critical can help to improve oneself but dwelling on all those negative aspects leads to a constant state of stress and chronic low self-esteem which, as we know, is detrimental to brain and physical health.

The other question to ask is whether this is a trait or state. Are some of us chronically low on self-esteem and have a shaky sense of self and are self-critical while others of us have a natural high sense of self-worth, sense of self, and are barely self-critical? Or is it state and domain specific i.e. depending on the context and situation – are we self-critical in some areas, domains, such as work, or sports, or with certain people? The research shows that it is a mix of these three as Zuroff et al. discussed in a meta-analysis in 2021. There is a strong element of trait self-esteem and self-confidence, but this is also influenced by situation, life stages, and contexts.

Of course, we can’t talk about self-criticism and self-love without talking about the other extreme and that of narcissism. It can also seem as if, for many, a sense of community, modesty, and sensitivity to others, leads us to avoid self-praise. Potentially for fear of being seen to be arrogant and “above” others. Modesty after all is universally considered a positive trait. And this is where self-love can truly become self-love and we become selfish narcissists. Observing the motivational literature this does not seem to be the case – people do not tend to go to a self-compassion meditation session and come out self-possessed narcissists – mostly due to the trait signatures we mentioned above (and meditation is often also focused on compassion for others).

However, two factors do point to society becoming more individualistic and narcissistic. One a recent piece of research showed that having choice makes us more selfish. The rise of social media and the selfie – has also given to an increase in narcissism – those who often post selfies are considered by peers to be more narcissistic. On the counter side we also know that it is the minority who engage so intensively with social media – teenagers as I noted earlier are particularly sensitive to social comparison so may tend to be more narcissistic also, as well as more self-critical, they are after all hyper aware of themselves.

Narcissism is viewed negatively in all societies but also has multiple negative effects with those who are most narcissistic being completely unaware of their shortcomings – however, in one study this was shown to be beneficial to themselves at least. Some of the happiest people it was shown are the most ignorant. Ignorance is bliss.

So far:

So where does this leave us? Well at this stage I would come back full circle to the SCOAP model, and some research done by Kernis at the start of the noughties. Kernis reviewed Self-Esteem and found a number of inconsistencies – for example being chronically low in self-esteem had fewer negative outcomes than having a wildly swinging self-esteem. Therefore, fragile self-esteem is more worrying on all levels: this is when we may desire high self-esteem, feel fantastic if we achieve something positive, but also are extremely sensitive to the downsides, beating ourselves up when we fail at something, or don’t achieve what we have set out to. Kernis therefore proposed authenticity as the key. He characterized authenticity as “the unobstructed operation of one’s true, or core, self in one’s daily enterprise.” He proposed four components to authenticity:

I would add to this, the idea of growth and a growth mindset. The above four aspects proposed by Kernis could without growth lead to stagnation. So, according to Kernis it is not necessarily loving oneself that is the key, it is accepting oneself, and importantly still having a growth mindset, so not letting this make you a static person with no growth potential. And with this self-awareness will likely also come realistic goal setting which is something I have learned to do for myself over the years and this has also lead to a more secure sense of self – yes this applies to my running also where I have set ambitious goals but am aware of how ambitious they are and any physical limitations – my times at various distances point to me being able, in theory at least, to run a faster 800m time.

Summary:

And so, with this and you may wonder how this applies to my running – by the time you read this I will probably be competing at the European Masters Athletic Championships (indoor). Well, I have realigned my goals based on my racing times this year. I have a clear racing strategy and a clear expectation – but also know that if it doesn’t work on the day, well, it doesn’t work. Whatever, I will enjoy the experience, meeting the other athletes, and being able to push my body to its limit – of which I am thankful. Will I be critical? A little, maybe…but then the focus will turn to the World Championships in June!

But back to healthy brains – though we know there is a trait-specific aspect of self-criticism, being overly self-critical leads to stress and in turn lower health and mental wellbeing outcomes. It is good when it drives you to higher performance and higher achievement, but if it leads to rumination and constant internal criticism it is not a good place to be. Learn to be kind to yourself – for your brain and your health!

Andy is author of leading brains Review, Neuroleadership, and multiple other books. He has been intensively involved in writing and research into neuroleadership and is considered one of Europe’s leading experts. He is also a well-known public speaker speaking on the brain and human behaviour.

Andy is also a masters athlete (middle distance running) and competes regularly at international competitions (and holds a few national records in his age category).

Self-Esteem

Eisenberger, N. I., Inagaki, T. K., Muscatell, K. A., Byrne Haltom, K. E., and Leary, M. R. (2011). The Neural Sociometer: Brain Mechanisms Underlying State Self-esteem. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 23, 3448–3455.

Gilovich, T., Medvec, V. H., and Savitsky, K. (2000). The spotlight effect in social judgment: An egocentric bias in estimates of the salience of one’s own actions and appearance. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 78. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.78.2.211.

Habermacher, A., Ghadiri, A., and Peters, T. (2015). Untangling Self-Esteem. Oral Present. 5th Eur. Coach. Psychol. Conf. 2015 December 11-12; London, United Kingdom.

Kernis, M. H. (2003). Toward a Conceptualization of Optimal Self-Esteem. Psychol. Inq. Vol 14(1), 1–26. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1401_01.

Kernis, M. H., Cornell, D. P., Sun, C. R., Berry, A., and Harlow, T. (1993). There’s more to self-esteem than whether it is high or low: the importance of stability of self-esteem. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 65, 1190–1204. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.65.6.1190.

Kolubinski, D. C., Marino, C., Nikčević, A. V., and Spada, M. M. (2019). A metacognitive model of self-esteem. J. Affect. Disord. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2019.05.050.

Leary, M. R., Tambor, E. S., Terdal, S. K., and Downs, D. L. (1995). Self-Esteem as an Interpersonal Monitor: The Sociometer Hypothesis. J. ol”Personality Soc. Psychol. 68, 518–530. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1403&4_15.

Self-Criticism

Aruta, J. J. B. R., Antazo, B. G., and Paceño, J. L. (2021). Self-Stigma Is Associated with Depression and Anxiety in a Collectivistic Context: The Adaptive Cultural Function of Self-Criticism. J. Psychol. Interdiscip. Appl. 155. doi:10.1080/00223980.2021.1876620.

Aruta, J. J. B. R., Antazo, B., Briones-Diato, A., Crisostomo, K., Canlas, N. F., and Peñaranda, G. (2021). When Does Self-Criticism Lead to Depression in Collectivistic Context. Int. J. Adv. Couns. 43. doi:10.1007/s10447-020-09418-6.

Campos, D., Cebolla, A., Quero, S., Bretón-López, J., Botella, C., Soler, J., et al. (2016). Meditation and happiness: Mindfulness and self-compassion may mediate the meditation-happiness relationship. Pers. Individ. Dif. 93, 80–85. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.08.040.

Halamová, J., Jurková, V., Kanovský, M., and Kupeli, N. (2018). Effect of a Short-Term Online Version of a Mindfulness-Based Intervention on Self-criticism and Self-compassion in a Nonclinical Sample. Stud. Psychol. (Bratisl). 60. doi:10.21909/sp.2018.04.766.

Hollis-Walker, L., and Colosimo, K. (2011). Mindfulness, self-compassion, and happiness in non-meditators: A theoretical and empirical examination. Pers. Individ. Dif. 50, 222–227. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.09.033.

Joeng, J. R., and Turner, S. L. (2015). Mediators between self-criticism and depression: Fear of compassion, self-compassion, and importance to others. J. Couns. Psychol. 62. doi:10.1037/cou0000071.

Löw, A. C., Schauenburg, H., and Dinger, U. (2020). Self-criticism and psychotherapy outcome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 75. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2019.101808.

Neff, K. D. (2011). Self-compassion, self-esteem, and well-being. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 5, 1–12. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00330.x.

Samaie, G., and Farahani, H. A. (2011). Self-compassion as a moderator of the relationship between rumination, self-reflection and stress. in Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.190.

Zuroff, D. C., Clegg, K. A., Levine, S. L., Haward, B., and Thode, S. (2021). Contributions of trait, domain, and signature components of self-criticism to stress generation. Pers. Individ. Dif. 173. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2020.110603.

Zuroff, D. C., Clegg, K. A., Levine, S. L., Hermanto, N., Armstrong, B. F., Haward, B., et al. (2021). Beyond trait models of self-criticism and self-compassion: Variability over domains and the search for signatures. Pers. Individ. Dif. 170. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2020.110429.

Narcissism

Littrell, S., Fugelsang, J., and Risko, E. F. (2020). Overconfidently underthinking: narcissism negatively predicts cognitive reflection. Think. Reason. doi:10.1080/13546783.2019.1633404.

Raskin, R., Novacek, J., and Hogan, R. (1991). Narcissism, self-esteem, and defensive self-enhancement. J. Pers. 59, 19–38.

Campbell, W. K., Hoffman, B. J., Campbell, S. M., and Marchisio, G. (2011). Narcissism in organizational contexts. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 21, 268–284.

Doty, J., and Fenlason, J. (2013). Narcissism and toxic leaders. Mil. Rev. 93, 55–60.

Zitek, E. M., and Jordan, A. H. (2016). Narcissism Predicts Support for Hierarchy (At Least When Narcissists Think They Can Rise to the Top). Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 7. doi:10.1177/1948550616649241.

Social Media and Society

Andreassen, C., Pallese, S., and D. Griffiths, M. (2017). Addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem. Addict. Behav. 64.

Fegan, R. B., and Bland, A. R. (2021). Social media use and vulnerable narcissism: The differential roles of oversensitivity and egocentricity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18. doi:10.3390/ijerph18179172.

Singh, S., Farley, S. D., and Donahue, J. J. (2018). Grandiosity on display: Social media behaviors and dimensions of narcissism. Pers. Individ. Dif. 134. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2018.06.039.

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.

When we talk of healthy brains we automatically think of things like exercise and nutrition that I have covered at times here. But the thing we put into the brain most is oxygen. So, let’s have a quick look at how the air we breathe impacts brain performance . . .

This content is only for Premium Brains - please subscribe to access this. All subscriptions come with a free trial.

Register for free to receive access to "Healthy Brains" and other selected articles.

Subscribe to Premium Brain (monthly or annual) to access all articles and access the download page.

Subscribe now