The standard logic in business and sports is that to get high-performing teams you should hire a bunch of high-performing individuals or even stars. In the sports world we are fascinated by this with fantasy teams of the best-ever teams of the best-ever players.

But the problem is that team performance is more than just the sum of the parts. For those who are familiar with rugby, which may not be many of you, every four years there is what is known as the British and Irish Lions tour. This is an old tradition and is considered one of the pinnacles of a rugby career – to play for and win with the Lions or play against and beat the Lions. In some ways more important and illustrious than the more recently introduced World Cup.

The fascinating thing is that logically the British and Irish Lions should thrash any team they come across. The players are selected from four of the biggest and most talented rugby nations on the planet (England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland). So, picking the most talented players from a talent pool four times the size for any national team should provide an extremely talented team. And yet, despite this, the Lions winning against another national team is a big thing and far from a foregone conclusion.

They selectively tour one of the southern hemisphere countries: South Africa, Australia, or New Zealand. On balance their chance of winning is only about 50/50 probability similar to if any one of the national teams were to independently tour. What’s more, as part of the Lions tour, they also play club or provincial teams – teams a step down on the pecking order of a national team and yet, surprisingly, maybe, they do not win all the time, or rather, they lose regularly.

This shows that despite having rich pickings of talent from four elite national teams they do not necessarily perform better than any one national team and still fail to beat lowly club teams.

The question is why not, and what is the difference?

Another question is that of the unspectacular person on the team who somehow enables high team performance. In his insightful article ‘The No-Stats All-Star’ in The New York Times Magazine in 2009, Michael Lewis captured the essence of the problem. Writing about the US National Basketball Association (NBA) player Shane Battier, he notes:

Here we have a basketball mystery: a player is widely regarded inside the NBA as, at best, a replaceable cog in a machine driven by superstars. And yet every team he has ever played on has acquired some magical ability to win.

The above story of Battier is fascinating because he was consistently classed as an underperformer, and quoted as “at best a marginal N.B.A. player”. His stats on the things that N.B.A. teams measure such as points and rebounds, were terrible. On paper he was a massive underperformer, but somehow when he was on the field everyone else performed better. The article that the above quote is taken from goes into a lot more depth on the refinement of statistical approaches and under some of these characteristics, or rather, better forms of statistical analysis, Battier does show up. For example, the greatest players all under perform when guarded by Battier. This may makes good reading for another article on statistical analysis or what we quoted in the previous article of “you don’t get answers to questions you don’t ask” or my concept of non-information.

There are now a number of issues to approach in the above examples.

-

- Groups of higher performers do not necessarily (and often don’t) make high performing teams.

- And that unspectacular performers, to the external eye, and to most statistical analysis, can enable teams to perform much better.

The question now in business, is how can we identify these, and can we reward them also? Or simpler how can we put together high-performing teams. And more than that how do we define “talent”?

Some of the clues may come in series of experiments on creativity. Tom Wujec is well known for his Ted talk on creativity using spaghetti and a marshmallow (a fun activity by the way) – the short video is well worth watching. The insights from these tasks are worth paying attention to. Notable is that kindergarten children were very effective but took a completely different approach to problem solving – worth saving for future articles on creativity – MBA graduates were terrible, and CEOs were also unspectacular.

Some of the clues may come in series of experiments on creativity. Tom Wujec is well known for his Ted talk on creativity using spaghetti and a marshmallow (a fun activity by the way) – the short video is well worth watching. The insights from these tasks are worth paying attention to. Notable is that kindergarten children were very effective but took a completely different approach to problem solving – worth saving for future articles on creativity – MBA graduates were terrible, and CEOs were also unspectacular.

Now let’s assume for the sake of argument, and there could be a lot of argument, that CEO’s and MBA graduates represent “talent”. Now not strictly true as Tom noted, thankfully, architects and engineers performed best and so were the most “talented”, giving thankful support, for the concept of being “an expert”. The CEOs and MBAs were ineffective because of using the wrong strategies – this is simply the problem of throwing a bunch of talented people together without thinking of team composition or what is known as complementarity. The insightful observation from Tom was that when he added an executive assistant to the teams of CEOs, their performance increased dramatically. Why?

He noted that communication and moderation increased. So, having a coordinator and communicator helped complementarity, and improved synchrony, another important facet of team performance. The assistants effectively functioned as enablers – similar to what Battier was doing – not worrying about their statistical performance but enabling others to perform better through managing communication and presumably also conflict effectively.

This is also neatly complemented by research into intelligence and collective problem solving by Woolley and colleagues: in a set of structured experiments teams were given collective problems solving tasks – tasks that required the team to solve a problem collectively. The outcome was that the team with the average highest IQ i.e. team packed with “talent” did not perform best, nor did the team with the person with the highest IQ, the top performer condition. So, who came out on top? The team with the best communication abilities, ability to listen and complement and interact with other people’s ideas. This again supports the concept of communication and enabling as being key factors to team performance. Women are more than interested to know that also simply having women in the team improved performance (of course you women knew that all along, didn’t you)!

There is more to team performance, the above is in collective problem-solving scenarios, which is not necessarily what every team is mandated to do, though arguably will always be a part of any team’s performance. Some of the other factors are not the focus of this article (see box at end). In summary team performance is very strongly influenced by other factors such as having a clear team, having clear roles, and clear goals. When I review teams in organisations, normally, this is the first thing I look at, and more often than not, the first thing that is wrong.

But in the case of Battier and the marshmallow exercise these were already given: the team was clear and the team goals also. But an important aspect of the research, often glossed over, is that individual competence was a predictor of individual productivity, but inter-team support was a better predictor of team productivity. Simply put, helping others in the team enables the team to perform better. This also points to a word of warning to those arrogant high performers. Though they may individually perform well, the question is how much do they diminish the performance of others? In sales teams, which are often loosely bundled teams, arrogant high performers may do little damage and create a lot of profit, but for interdisciplinary teams looking to create new solutions, the team damage is likely to override their individual ability.

But in the case of Battier and the marshmallow exercise these were already given: the team was clear and the team goals also. But an important aspect of the research, often glossed over, is that individual competence was a predictor of individual productivity, but inter-team support was a better predictor of team productivity. Simply put, helping others in the team enables the team to perform better. This also points to a word of warning to those arrogant high performers. Though they may individually perform well, the question is how much do they diminish the performance of others? In sales teams, which are often loosely bundled teams, arrogant high performers may do little damage and create a lot of profit, but for interdisciplinary teams looking to create new solutions, the team damage is likely to override their individual ability.

This, however, doesn’t lead us into any insights of how to actually identify these people or team dynamics – obviously the intuitive amongst us will already have identified this and may make better decisions on team fit and include this in hiring decisions. But some research (unpublished) we did on successful and failed teams in the startup space gives us some intriguing theories of team performance. This could also give us better analytics such as in the example of Battier that showed with standard analytics he was an underperformer but when using more refined methods he was an exceptional performer.

We only measured personality with a view in our first mandate to give some ideas of how well-matched startup teams were. The reason for our first piece of research into this was the acknowledged importance of the team in enabling startups to succeed but an inability or unwillingness to measure this. So, what did our research show?

First off, we looked at the concept of homophily. This is the concept that similar personalities get on well with each other. We set some cut-off points and first off, we could see that areas of conflict that we predicted with high variation in personality, was well-supported.

However, there is a problem with this because of the two concepts I mentioned previously. Namely synchrony can be seen as how similar in personality, or mindset, individuals are, but complementarity is the concept of having differing but complementary skills or personality traits. These are seemingly contrasting aspects. Though many leaders proudly claim they have diverse teams, our research shows they are not as diverse as they like to think, because they may be similar in multiple aspects of personality. Before I digress too far, I am sure you are keen to learn of what else we discovered in personality and effective teams.

However, there is a problem with this because of the two concepts I mentioned previously. Namely synchrony can be seen as how similar in personality, or mindset, individuals are, but complementarity is the concept of having differing but complementary skills or personality traits. These are seemingly contrasting aspects. Though many leaders proudly claim they have diverse teams, our research shows they are not as diverse as they like to think, because they may be similar in multiple aspects of personality. Before I digress too far, I am sure you are keen to learn of what else we discovered in personality and effective teams.

Well, we found that:

-

- Similarity in personality predicted cohesion

- Differences in personality were well accepted best when only in limited areas. So, the larger the differences, and the larger the number of traits that differed, the worse the team cohesion.

- Extreme differences can cause conflict particularly when in multiple areas.

- Polarisation was an important aspect of team conflict i.e. when two members were high in a trait and another very low.

- Individualisation of polarisation – when a single person is an outlier it can lead to this person being left out, when it is multiple this person can be totally polarised.

- Large variations, if evenly distributed, can lead to cohesion but slow decision making. So, the opposite of homophily when there is wide but nicely distributed spread there may be some underlying conflict, but everyone balances each other out. Complementarity in short

- Mindset caused large disruptions. For example, we mapped team members to corporate mindset, based on traits that support classic corporate thinking, and startup mindset, and this was very predictive of conflict and team breakup in the startup scenarios.

- Some traits seemed more predictive than others e.g. multiple personalities high on dominance was a recipe for conflict

- “Typing” (such as classic personality assessment humanistic vs. cognitive types) is too general and much less effective than including multiple different single traits

From this we developed a coherence figure including the above multiple inputs – but this can only be understood as a rough guide to team cohesion because a team has many moving parts. Roles, as we said, play a key importance and being effective in roles is critical for cohesion and conflict minimisation – we don’t measure this. Similarly, leadership and reporting structures will also guide potential for conflict.

What we also found, however, is that there are also moderating traits that minimise the risk of conflict. These includes, openness, and humour and those individuals who are high in intuition and high in cognition, helping to mitigate between these two contrasting viewpoints.

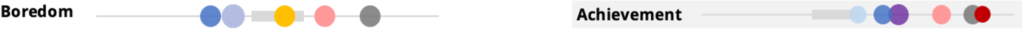

With the question of how to identify those average performers who enable high performance, let me show you what happens when we remove one person from a team.

Here you can see two teams along two separate personality traits (note that we measure up to 72 personality traits with our HBF tool – but normally only 28 for team cohesion). What you can see is a distribution of personalities along a scale. This team is therefore, based on this one trait, likely to differ significantly in how they approach problems and see the world but there are a range of personalities so there are those in the middle who will moderate others and act as communicators between the two. Decision-making may be slow but could be effective.

Team with balanced personality distribution

However, if we move one person out of the team, in each case the middle person, we now suddenly have a polarized team with two groupings and high and low ends of the scale. Polarisation was one of the biggest predictors in our data for team conflict. So, by removing one person from the team we have now created the potential for more conflict. This could therefore be the unspectacular performer who unbeknownst to others helps moderate conflict.

Team with moderating personality removed and with increased polarisation

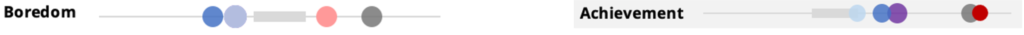

The level of polarisation in the above is not extreme, here another example from the real world with very high polarisation:

A highly polarised team

So where does this leave us? Let me summarise

-

- A collection of talent or high performers does not make a high performing team

- Synchrony and complementarity are critical to team performance

- These can be measured and mapped but never are

- Communication skills are critical

- The team leader is responsible for managing this complementarity and synchrony

- Personality awareness can improve synchrony and complementarity

- Level of inter-team support is predictive of team performance

- Don’t forget the other obvious factors such as clear roles and clear goals

In short, when looking to build high-performing teams look to high synchrony and high complementarity (over, and with, “high talent”), measure this, build awareness, encourage open communication. And, food for another article another day, you need a team leader who can manage and lead this effectively.

The corporate problem is that many organisations seem unaware of these team performance issues, still focusing on getting “talent” and measuring individual performance. A question to ask, is how to measure, and value team performers, and how do you reward those individuals who may be unspectacular but somehow keep the team rolling? A good start is to measure team cohesion but also to identify those who are the enablers in the team and have high inter-team behaviours – they may be worth a lot more than you think●

Some of the clues may come in series of experiments on creativity. Tom Wujec is well known for his

Some of the clues may come in series of experiments on creativity. Tom Wujec is well known for his  But in the case of Battier and the marshmallow exercise these were already given: the team was clear and the team goals also. But an important aspect of the research, often glossed over, is that individual competence was a predictor of individual productivity, but inter-team support was a better predictor of team productivity. Simply put, helping others in the team enables the team to perform better. This also points to a word of warning to those arrogant high performers. Though they may individually perform well, the question is how much do they diminish the performance of others? In sales teams, which are often loosely bundled teams, arrogant high performers may do little damage and create a lot of profit, but for interdisciplinary teams looking to create new solutions, the team damage is likely to override their individual ability.

But in the case of Battier and the marshmallow exercise these were already given: the team was clear and the team goals also. But an important aspect of the research, often glossed over, is that individual competence was a predictor of individual productivity, but inter-team support was a better predictor of team productivity. Simply put, helping others in the team enables the team to perform better. This also points to a word of warning to those arrogant high performers. Though they may individually perform well, the question is how much do they diminish the performance of others? In sales teams, which are often loosely bundled teams, arrogant high performers may do little damage and create a lot of profit, but for interdisciplinary teams looking to create new solutions, the team damage is likely to override their individual ability. However, there is a problem with this because of the two concepts I mentioned previously. Namely synchrony can be seen as how similar in personality, or mindset, individuals are, but complementarity is the concept of having differing but complementary skills or personality traits. These are seemingly contrasting aspects. Though many leaders proudly claim they have diverse teams, our research shows they are not as diverse as they like to think, because they may be similar in multiple aspects of personality. Before I digress too far, I am sure you are keen to learn of what else we discovered in personality and effective teams.

However, there is a problem with this because of the two concepts I mentioned previously. Namely synchrony can be seen as how similar in personality, or mindset, individuals are, but complementarity is the concept of having differing but complementary skills or personality traits. These are seemingly contrasting aspects. Though many leaders proudly claim they have diverse teams, our research shows they are not as diverse as they like to think, because they may be similar in multiple aspects of personality. Before I digress too far, I am sure you are keen to learn of what else we discovered in personality and effective teams.