The Dramatic Impact of Poverty in Newborns Brains Reading time: about 5 minutes o, does being poor impact your brain, or are people with decreased cognitive ability poor? Some people may have strong opinions on the above question. Probably broadly...

How Poverty Messes Up Babies’ Brains

The Dramatic Impact of Poverty in Newborns Brains

Reading time: about 5 minutes

So, does being poor impact your brain, or are people with decreased cognitive ability poor?

Some people may have strong opinions on the above question. Probably broadly along political partisan lines. But the best place to answer this question is with research and science and the answer is coming firmly down on the side of, poverty disrupts you brain. If I were being dramatic, I might say it “wreaks havoc” “destroys” or some other emotional descriptions. They might actually be very good descriptions.

But how?

First, let’s review some recent research out which is really interesting because it scanned newborn babies’ brains while they were sleeping. This is really important because it showed that this life disadvantage is there right from day one. That is very worrying.

The researchers at Washington University School of Medicine analysed a sample of 399 mothers and their babies. 280 of these were at a social disadvantage - scientific language for being poor. And these newborns showed significant differences to their brains to babies born to mothers in better social conditions.

The scans showed

- Less cortical gay matter - cortical gray matter is the outer layer of the brain considered our higher functional area of the brain (but involved in a lot including sensory processing). The gray matter is the area that houses your neurons, brain cells.

- Less sub-cortical gray matter – subcortical gray matter refers to regions that sit in the internal regions of the brain which are often important for emotional functions but also memory and general functional processing. As I said, gray matter houses your neurons, brain cells

- Less white matter - white matter refers to the mass of connections between brain regions. So, this suggests less connections between all brain regions, or less efficient connections.

- Fewer and shallower folds in the brain – the folds in the brain give it that wrinkly look and allows the brain to have more surface area but is also a sign of a mature or more functional brain.

This is quite dramatic – though the absolute differences may not be large, it all points to a less developed, or functional brain, at all levels. This was simply comparing two groups of newborns shortly after birth. This means these babies are at a disadvantage right from the outset - even before anything else happens these kids are starting at -1.

This is worrying and another study from the same dataset asked another question.

How does crime exposure affect newborns’ brains?

For this study they analysed what neighbourhoods these pregnant women lived in and hence their potential exposure to property or violent crime. And the results again are worrying. But the results were different: in the aforementioned study the results seemed to impact the whole brain and not specific regions of it but in this study various functional networks were affected.

A number of networks were affected but the most relevant is that of the thalamus-amygdala-hippocampus network. This may sound like gobbledygook to you but this is a network that connects sensory information to emotional responses and to memory functions. So, in short disrupted emotional and memory networks.

The same applies as to the previously mentioned study. This was in newborns with just the mothers living in higher crime neighbourhoods – just this was enough to see a significant difference in these newborn babies’ brains.

So, those kids born in poverty with these mothers being exposed to crime during pregnancy seem to be starting life at -2. Decreased brain maturity and disrupted emotional and memory networks. Not good, very bad indeed.

It is also really important to note that we haven’t even begun to speak about developmental factors and how these brains can and do develop in socially deprived environments, nor have we spoken about epigenetics, such as how stress can pass an gene activation patterns to offspring.

This also shows that breaking out of this cycle requires more than just proclaiming that people need to make the good choices in life. Of course, they do, but starting out with a brain that is already less developed and with disrupted networks is only likely to perpetuate this poverty cycle.

What about brain development?

We do know, of course, that there are many developmental factors that can and do contribute to brain development of children in positive ways. In this article here I outline the ground-breaking research that showed that care for children could massively boost IQ.

The Abecedarian Project in the USA showed that pre-school education could leave traces in the brain that could be seen 50 years later. Similarly, breast feeding has been shown to improve the brain health of children and also of mothers – and, again, this can be seen decades later in the brain. In addition, exercise and movement improves children’s brain signatures – with exercise in pre-teen years leaving a signature on the brain also observable many years later.

That is all good but what the observant amongst you will notice is these are also often related to social standing.

Pre schooling - particularly high quality pre schooling is basically only available for those who can afford it or live in the right neighbourhoods. High quality nutrition also.

Breastfeeding may seem like a cheap option to help with your kids’ brain development, but this necessitates actually being able to breastfeed with your children, the mother having the right nutrition, and being able to do this. If a mother is living in poverty and trying to hold down two jobs to feed herself and her children, this may be out of the question. And often is.

Similarly, taking part in structured sporting activities is something that comes with social settings - but it is something that could be a cost-effective intervention for many children.

A just society?

So, if we do want a society that can grow and flourish, if we want a just society, if we want a good society, we should pay close attention to this.

Development of children’s brains happens before they are born - interventions that help pregnant mothers, particularly those who are impoverished, will have a significant benefit on those babies’ brains. Similarly investing in interventions pre-school also.

The worrying take-away, and important message, is that poverty really does mess with your brain. It does this as an adult but more importantly, as I have just outlined, based on scientific evidence, it messes with your brain right from the outset - from before you are born.

This also massively raises the importance of investing in and enabling interventions at this stage – guided by science rather than political opinions.

After all who wouldn’t want a society with better brains. I do●

Andy Habermacher

Andy is author of leading brains Review, Neuroleadership, and multiple other books. He has been intensively involved in writing and research into neuroleadership and is considered one of Europe’s leading experts. He is also a well-known public speaker speaking on the brain and human behaviour.

Andy is also a masters athlete (middle distance running) and competes regularly at international competitions (and holds a few national records in his age category).

References

Regina L. Triplett, Rachel E. Lean, Amisha Parikh, J. Philip Miller, Dimitrios Alexopoulos, Sydney Kaplan, Dominique Meyer, Christopher Adamson, Tara A. Smyser, Cynthia E. Rogers, Deanna M. Barch, Barbara Warner, Joan L. Luby, Christopher D. Smyser.

Association of Prenatal Exposure to Early-Life Adversity With Neonatal Brain Volumes at Birth.

JAMA Network Open, 2022; 5 (4): e227045

DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.7045

Rebecca G. Brady, Cynthia E. Rogers, Trinidi Prochaska, Sydney Kaplan, Rachel E. Lean, Tara A. Smyser, Joshua S. Shimony, George M. Slavich, Barbara B. Warner, Deanna M. Barch, Joan L. Luby, Christopher D. Smyser.

The Effects of Prenatal Exposure to Neighborhood Crime on Neonatal Functional Connectivity.

Biological Psychiatry, 2022

DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2022.01.020

More Healthy and Society Brains articles

How Poverty Messes Up Babies’ Brains

Two Hopeless Little Girls Abandoned to a Mental Institution — With Astounding Results

An Astounding and Underated Story of Brain Development Reading time: about 7 minutes he story goes that Harold M. Skeels, on taking over responsibility for the Iowa state psychiatric institutions in 1938, walked into the Iowa State orphanage which...

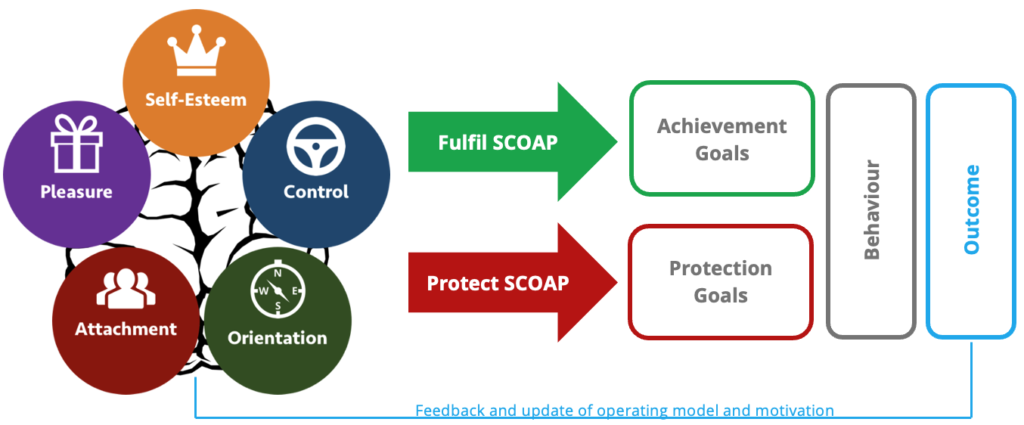

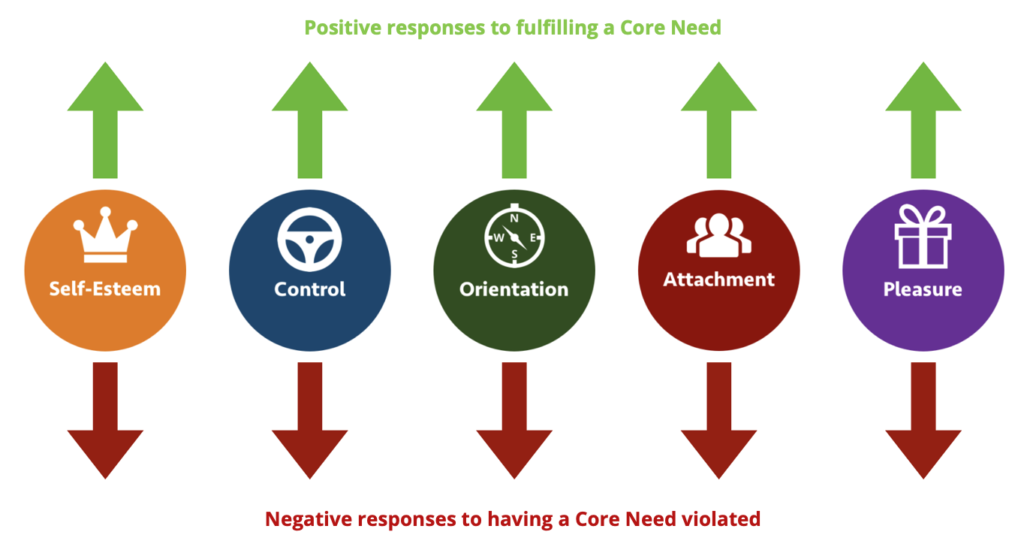

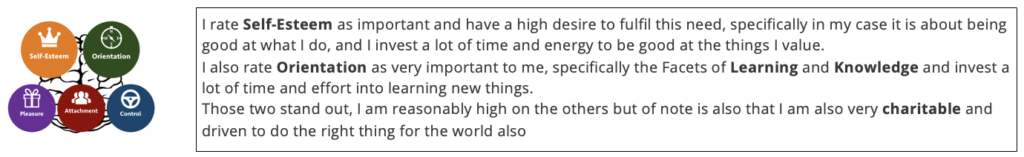

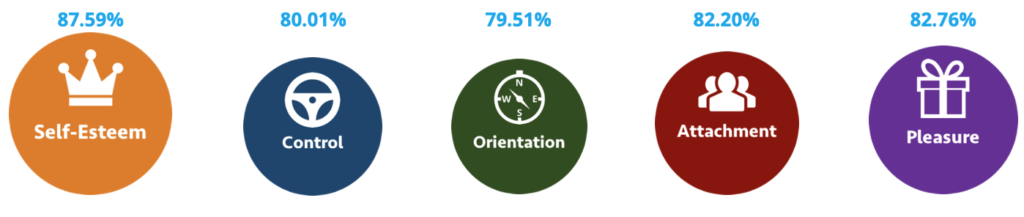

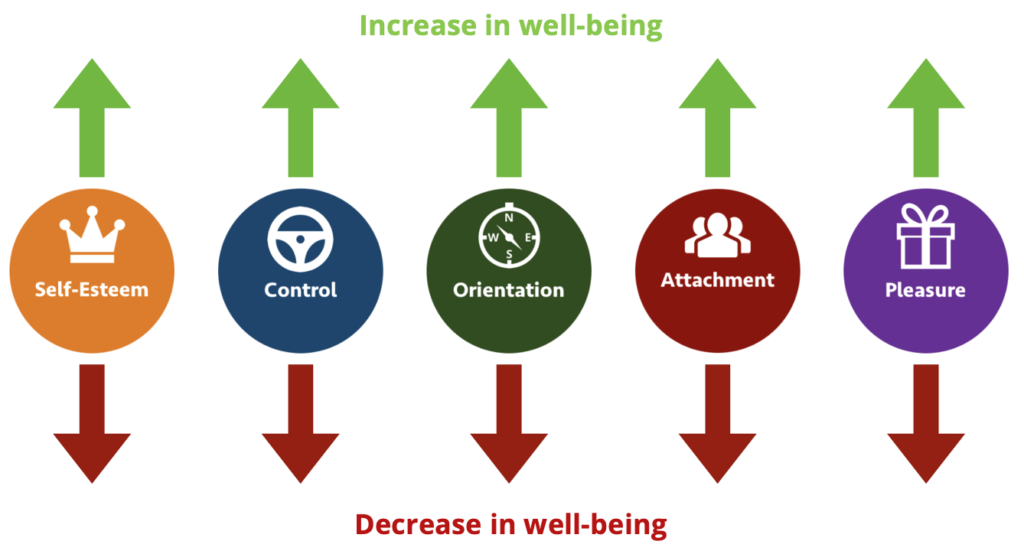

SCOAP An Introduction

A comprehensive theory of human motivation, behaviour, and well-being What is SCOAP? SCOAP is a complete model of human motivation, behaviour, and wellbeing, summarising over a century of research into the human brain and human behaviour in all contexts. SCOAP is an...

Eat Less to Live Longer

When we talk of healthy brains we automatically think of things like exercise and nutrition that I have covered at times here. But the thing we put into the brain most is oxygen. So, let’s have a quick look at how the air we breathe impacts brain performance.

Lower smartphone usage increases wellbeing

So much has been said about smartphone usage in modern times. This ranges from some who say that they are destroying our brain to others who see they benefit our cognition by outsourcing cognitive heavy tasks like remembering lists of phone numbers – thereby freeing...

Team Conflict

Managing conflict is an essential skill – but is having conflict essential? There is a lot to be said about having a good argument. You can clean the air and resolve major emotional issues. However, when in a heated argument you may also damage relationships. Some...