Why the “aha” moment is overrated

Reading time: about 4 minutes

Creating the “aha effect” – that effect of “the penny dropping” sounds intuitively to be a really good thing in teaching and when training. But hold your horses – looking into the brain and how the brain builds connections, we can see that a slower effect starting out with confusion and leading to a self-initiated understanding may be even more powerful.

When I first started teaching there was nothing more that I enjoyed more than seeing my students (adults in my case, mostly) light up as they “clicked” and got something. Similarly, when I do public speaking it is great to see the audience clearly getting it and the lights going on their heads. This can be called different things at different times but mostly the ”aha” effect, when the penny drops, that feeling of understanding.

And so it was, as a teacher I was always, initially, at least, on a constant search to enable this aha effect. Sometimes this was easier, sometimes it remained elusive. Similarly, as I progressed and moved into delivering corporate workshops and public speaking, I looked to create those aha moments. Sometimes we are aiming to create a deeper awareness something that resonates with the soul, so to speak. But more often than not it is still the search for those aha moments.

And this is something that all corporations expect and demand when I am requested to speak or give workshops, trainings, or webinars – to give some “clear takeaways”. People have to be able to get it, to understand, and have a few strategies to be able to implement the learnings. This all sounds reasonable and logical. Unless, that is, we look at the brain – we can then see that, maybe, we are not doing the brain, the person, and the concept of learning any favours. In fact, by giving clear takeaways, clear learning goals, we may even be inhibiting learning! You won’t be convinced at this stage – this is not the ramblings of a middle-aged man – let me explain just why we may be doing the audience, students, a disservice.

This first came to the forefront in 2012 when researchers at the University of Notre Dame in the US showed that confusion can be beneficial for learning. Why would that be the case? This is because certainty and the aha moments effectively shut down the brain. The brain no longer has to try to resolve the problem. If you are in a state of confusion your brain will consciously and unconsciously try to resolve this and therefore work harder to resolve this confusion. The brain doesn’t like this state which is why it remains active. Therefore confusion, preferably carefully induced, or not too severe, can be beneficial to learning.

The second point is that because the brain has to work harder for longer to resolve the confusion the learning is likely to be deeper and more solidly learnt. The brain has to engage more resources and therefore this could also benefit other areas of learning. Simply put, making it harder, increases the benefits.

The third point is speculative on my part – but would make sense. My assumption is that by the process of resolving confusion we are engaging in implicit “confusion resolution mechanisms” and this can benefit learning in multiple other contexts. We are training cognitive skills that have diffuse but wide-reaching consequences and benefits.

A fourth point is that this may be the process the brain goes along all the time. For example, some creativity research (into that aha moment or flash of insight when solving a problem) shows that the process of making progress toward a solution is mostly an unconscious process, but the progress is nevertheless important. If I am trying to solve a problem, I may move from step one to step six out of a hypothetical ten (with ten being the solution or flash of insight). I have made progress but may not be aware of this progress, however, my brain is six steps closer to resolving the problem. When I hit ten, I have that flash of insight and think “aha”, it is resolved – but the process of moving through stages one to nine have been critical to this – I may, however, only remember step nine to ten.

The final point is that these processes are self-processed, and self-initiated and we know from the research that self-initiated processes are more powerful for learning and retention. What’s more this can build confidence and pride much more strongly than simply remembering what was told or that quick aha moment which was guided by a third person.

So, to really activate the brain and learning we should be aiming, at times, to induce confusion and allowing self-initiated resolution of this. Leaving students and learners in a state of confusion can be incredibly beneficial to learning – there is a negative feeling associated with this and this may need to be managed (for example, encouraging learners to sit with the problem, to avoid negative emotions, to trust one’s brain, etc.). A word of warning – this confusion should not be persistent. Indeed, the type of confusion and ensuing support is also critical according to further research – just confusing the hell out of course participants, an audience, and students is a bad approach – sorry no free card here. Carefully inducing confusing aspects, paradoxes, and then helping and guiding learners to resolve this is the approach that boosts the impact of learning.

“Confusion interventions are best for higher-level learners who want to be challenged with difficult tasks, are willing to risk failure, and who manage negative emotions when they occur.”

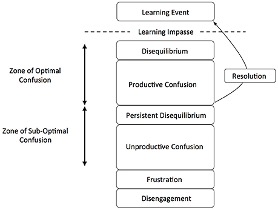

Lodge et al. in a 2018 review give a model of optimal confusion (below). This highlights that optimal confusion which enables resolution is best but high levels of confusion can cause frustration and disengagement.

Model of optimal confusion by Lodge et al. (2018)

Let’s summarise

-

- Intentionally inducing confusion can boost learning

- But enable participants to manage this process and the negative emotional state (e.g. by learning to sit with unknowing)

- Guidance may need to be given

- Enable resolution

- Model processes that enable resolution e.g. by having an incubation period

- If confusion is too great this may backfire (don’t just confuse the hell out of people)

So, confusion is a powerful tool for enhancing learning and this is why some aspects of training and teaching could be approached differently. Enabling self-discovery and self-initiated discovery and going through these cognitive processes are not only beneficial for learning but have wide-reaching applications in real life by enabling general cognitive strategies to resolve complexities in the real world – the world is generally a complex place. But in the training or teaching contexts this must be carefully managed to enable resolution of confusion and the learning impact. And this is why I say that slightly confused is a good place to be●

References

Confusion

D’Mello, S., Lehman, B., Pekrun, R., and Graesser, A. (2012). Confusion can be beneficial for learning. Learn. Instr. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2012.05.003.

Lehman, B., D’Mello, S., and Graesser, A. (2012). Confusion and complex learning during interactions with computer learning environments. Internet High. Educ. 15. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2012.01.002.

Lehman, B., D’Mello, S., Strain, A., Mills, C., Gross, M., Dobbins, A., et al. (2013). Inducing and Tracking Confusion with Contradictions during Complex Learning. in International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education doi:10.3233/JAI-130025.

Lodge, J. M., Kennedy, G., Lockyer, L., Arguel, A., and Pachman, M. (2018). Understanding Difficulties and Resulting Confusion in Learning: An Integrative Review. Front. Educ. 3. doi:10.3389/feduc.2018.00049.

Zhang, Y., Bosch, N., Paquette, L., Munshi, A., Baker, R. S., Biswas, G., et al. (2020). The relationship between confusion and metacognitive strategies in Betty’s Brain. in ACM International Conference Proceeding Series doi:10.1145/3375462.3375518.

Flash of insight

Sawyer, K. (2011). The Cognitive Neuroscience of Creativity: A Critical Review. Creat. Res. J. 23, 137–154. doi:10.1080/10400419.2011.571191.

Sawyer, R. K. (2007). Group Genius: The Creative Power of Collaboration. INDUSTRIAL RESEARCH INST, INC.

Zenasni, F., Besancon, M., and Lubart, T. (2008). Creativity and Tolerance of Ambiguity : An Empirical Study. J. Creat. Behav. 42, 61–73.

Self-Efficacy and Learning

Agustiani, H., Cahyad, S., and Musa, M. (2016). Self-efficacy and Self-Regulated Learning as Predictors of Students Academic Performance. Open Psychol. J. 9. doi:10.2174/1874350101609010001.

Komarraju, M., and Dial, C. (2014). Academic identity, self-efficacy, and self-esteem predict self-determined motivation and goals. Learn. Individ. Differ. 32, 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2014.02.004.

Kustyarini, K. (2020). Self efficacy and emotional quotient in mediating active learning effect on students’ learning outcome. Int. J. Instr. 13. doi:10.29333/iji.2020.13245a.

Zimmerman, B. (2000). Self-Efficacy: An Essential Motive to Learn. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 25, 82–91. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10620383.