Quick Hits

Daily brief research updates from the cognitive sciences

One differentiating factor with human beings is our pro-sociality. This means we are a social species, and this sociality is seen in our ability to empathise, be socially tolerant, but also in our cooperation and altruism.

The question then comes: what drives this behaviour and is this really different to other species? The second question is whether this is also different to other earlier human forms such as Neanderthals and Denisovans. To find that out researchers at the University of Barcelona did a genetic analysis of non-human primates such as chimpanzees and bonobos and also archaic humans.

How did they do this?

First off, they focused on genes that they know contribute to this pro-sociality. We know that these come along two pathways and are related to Oxytocin and Vasopressin (see box at end of article) – both of these hormones are heavily involved in various social behaviours such as friendship and romantic bonding, but also trust and loyalty.

Next was to identify functional sites of these genes and to see compared to other species and archaic humans if there were any differences.

What did they find?

They found, first, differences to modern and archaic human beings and non-human primates showing that various social functions seem to be different in modern or archaic humans.

Second, they found that there are two sites whereby modern human beings differ to archaic human beings showing that our sociality has also developed over time. It suggests that modern human sociality is much higher, or more advanced, and this is also likely one of the reasons why modern human beings have evolved and possible outcompeted other earlier human lines.

Third, these sites are also regions that are active in the brain particularly an area called the cingulate cortex which is a site that is associated with multiple social processing networks in the brain but also social deficits.

Human being, social being

So, all in we can see that human beings are social like many species, but that we differ in genetic expression to non-human primates but also to archaic humans. It is indeed our oxytocin that makes us particularly social and allows us to coordinate in groups, build a wide variety of friendships, to bond with others, to empathise, and to be charitable. There is also a downside to this, such as coordinated violence, which I explore in my article here on oxytocin.

So, all this points to, yes, human beings are special, and especially because of our sociality●

Oxytocin – the cuddle hormone?

Oxytocin, a hormone and neuromodualtor, has received a lot of popular press over the years. One of these reasons is that it is invovled in many aspects of sociality. This attracted a lot of publicity when it was found that in voles, field mice, that mongamy and loyalty between pairs of voles was directly influenced and could be manipulated by oxytocin. Increase oxytocin and they become more monogamous and loyal to each other, and reduce oxytocin and this decreases. Was this the key to monogamy?

Well, kind of, but, as with all things, it is more complicated than that. But the upshot of this was a bunch of resarch into oxytocin that showed how it could influence bonding, feelings of warmth, and cuddling. It was also noted that many of these things in turn stimuatle oxytocin such as stroking your baby, a romantic partner, or even your pet.

Research then also branched into economic scenarios with some research showing oxytocin increases trust between strangers in financial scenarios.

Oxytocin is definitely strongly related to many social functions but also many physiolgical functions – it stimulates labour in women during childbirth and promotes milk production in new mothers. But oxytocin has also other effects – read here for a more detailed overview.

Andy Habermacher

Andy is author of leading brains Review, Neuroleadership, and multiple other books. He has been intensively involved in writing and research into neuroleadership and is considered one of Europe’s leading experts. He is also a well-known public speaker speaking on the brain and human behaviour.

Andy is also a masters athlete (middle distance running) and competes regularly at international competitions (and holds a few national records in his age category).

Reference

Constantina Theofanopoulou, Alejandro Andirkó, Cedric Boeckx, Erich D. Jarvis.

Oxytocin and vasotocin receptor variation and the evolution of human prosociality.

Comprehensive Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2022; 11: 100139

DOI: 10.1016/j.cpnec.2022.100139

More Quick Hits

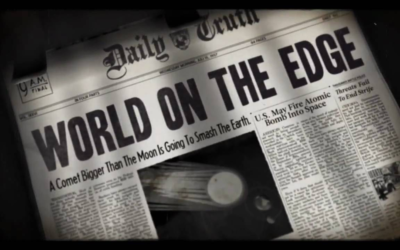

News Addiction is Bad for Your Mental (and Physical) Health

Many years ago I first heard the advice of “Don’t watch the news if you want to be happy”…

Fresh Teams are More Effective and More Innovative

We all know that just about anything in the world is produced by teams. This has never been more true than in scientific disciplines…

Too Much of a Good Thing – Why Leaders Can be Too Extraverted

Extraversion is considered a positive trait particularly in leadership – but can there be too much of a good thing?

Gene Mutation Leads to Being “Clueless”

Researchers at the UT Southwestern Medical Centre have discovered a genetic mutation that impacts memory and learning.

Humble Leaders Make Teams More Effective

This study showed that those in groups with leaders who showed the highest humility reported multiple positive results all of which can be directly correlated to higher performance.

Micro Breaks Improve Performance and Wellbeing

We all know that taking breaks is good for our brain and wellbeing – in fact we absolutely need to take breaks. It is just the way our brain and body is designed.